When Giant announced that the Lafree Twist (hereafter referred to as the Lafree to avoid confusion) was to be replaced,we were somewhat sceptical. Despite a few quirks, the old bike was light, efficient,and much loved – clearly it would take some beating.

The new bike was launched first in The Netherlands and Germany last year,and information has been oozing out ever since.It seemed the motor was a derivative of the Sanyo front hub motor we’d rather disliked on the cut-price Giant Suede,and there were two battery options heavyish,cheapish NiMH on the Twist 2.0, and state-of-the-art Liion on the Twist 1.0.In both cases,the bike carried two batteries, and the range was claimed to be phenomenal – ‘up to’ (we see that phrase a lot) 100 miles.There was also a suggestion of regenerative braking. Finally,we have a sample.Is it all true?

The Twist 1.0

Giant may be based in Taiwan,but it’s a truly global company,and where models are aimed at a specific market,the big cheese in Taipei wisely opts to use local knowledge. This wasn’t true of the original Lafree,an ugly, brutish creature,but the ‘classic’ Lafree and the new Twist have both been designed in The Netherlands,and it shows.

The Twist is a huge machine – high in the saddle and even higher in the handlebars.Ours has a medium frame,and most people can ride it,so the three options should cover one and all. Handlebar height is taken care of by a Tranz-X adjustable stem,giving adjustment from 110cm to 123cm on our bike.

And in true workaday Dutch style,it’s well equipped:suspension,full lights (battery LED at the rear and traction-battery powered halogen at the front),mudguards,centre stand,panniers,chain guard,wheel lock,and the latest Nexus 8-speed hub.In The Netherlands,this spec would be nothing special,but it’s rare in the UK.And,of course,this one has assistance too – behind the panniers (and sort of inside too,but we’ll come to this) are twin 27 volt Li-ion manganese oxide power packs of 270 watt/hours each.If that sounds like a chemistry lesson,the total 540Wh capacity is nearly three and a half times that of the superseded Lafree,and one of the biggest electric bike packs around.In other words,it should go quite a long way.These batteries are high-tech stuff,weighing only 2.6kg apiece.In terms of weight efficiency,the NiMH battery on the 2006 bike offered a reasonable 40 watt/hours per kilogram,but the new ones pack 104 watt/hours per kilogram.

The bike itself is a bit heavier than the Lafree,weighing 24.9kg,against 18 – 22kg.Add the pair of batteries,and the 2007 model weighs 30.1kg (66lb),against a class-leading 22kg (48lb) for the old Lite model.The good news is that it’s more rigid.The chunky,but beautifully finished alloy frame making the Lafree look a bit spidery.Oddly,the main tube is made to a ‘U’ profile,being open underneath,but there’s plenty of strength there.

First Impressions

The Sanyo front hub motor is based on the Electric Wheel,designed by O J Birkestrand of the Rabbit Tool Co,Illinois (see A to B15 ).This design showed great promise,but the road from prototype to production can be rocky,and the production version is not quite so clever.It’s an AC motor that’s permanently engaged,which enables it to provide power to get you up hills,and reabsorb power down the other side,but unlike a direct drive motors fitted to the BionX or Ion,the Sanyo has internal gears.To work quietly and without friction,these gears have to be very well engineered,and in practice we found the Suede’s Sanyo motor noisy and aggravatingly slothful.This one is much better,and actually quieter than the Lafree,but by modern standards it’s noisy,with a shade too much drag. We could forgive this if it offered regenerative braking,but as we’ll see,it doesn’t.

…the Nexus 8-speed is one of the best… the gear range is better, the number of gears is increased…

First impressions are that the crank feels strangely ‘cushioned’.This is caused by the sensing mechanism,which judges how hard the rider is pedalling.Like the old Lafree,this bike is a pure pedelec, meaning that the motor will only function if you’re putting in a reasonable amount of effort,so it isn’t suitable for those who don’t want to,or are perhaps unable to,turn the pedals.You get used to it,but in this area the Lafree won hands down,because it had a superb sensing mechanism – the best and most ‘conventional’ we’ve come across.

Another slightly odd sensation is of the front tyre ‘tram lining’ on the road surface.In fact,this is quite harmless and caused by a return spring,biasing the front wheel to the straight ahead position.It’s a useful feature when the bike is on the stand,protecting the motor cable from being stretched,but some people may be unnerved by the handling quirks.

The Nexus 8-speed hub gear is one of the best around,and certainly an improvement on the 7-speed Nexus fitted to the cheaper Twist 2.0.It’s usually possible to pedal right through upward changes,as you would with a derailleur – something you can’t always do with the Sturmey 8 or SRAM 7.But,human nature being what it is,you end up pushing the technology by doing it every time, and once in a while the hub gets caught out,producing a nasty clunk. We were also a bit disappointed by the gaps between gears,which vary wildly.We have no objection to a 22% gap between Gears 1 and 2,but are less keen on 14% between Gears 7 and 8, where a big gap can be useful. The hub is adjusted by lining up two yellow pointers in Gear 3, but they’re under the hub,and in this case,inside the chainguard which has to be partially removed.

The old Lafree Lite was fitted with a 3-speed Nexus,which didn’t give a wide enough range,and the more expensive models came with the 4-speed Nexus (more gears,same range),and later the 5-speed and 7-speed SRAM.On the new bike,the gear range is better,the number of gears is increased,and as the motor output takes a different route to the road,hub life should be improved definitely a plus point.

Gearing is about right for a bike of this kind.At 29 inches,first is low enough for most eventualities,even without assist,and at 89 inches,top is just up to fast riding,although another few gear-inches would be welcome.As usual with a Giant electric bike,power melts away at precisely 15mph,but the squidgy pedals and the constant drag mean you’re unlikely to voluntarily pedal any faster.The extra drag is little more than a dynamo,but it’s annoyingly noticeable,and several people observed that the Twist felt slower than the Lafree.It isn’t,but the drag makes it feel as though it is.Strangely,the resistance seems to melt away at very high speed,and the bike thunders down steep descents – we saw 40mph on two occasions.

On the Road

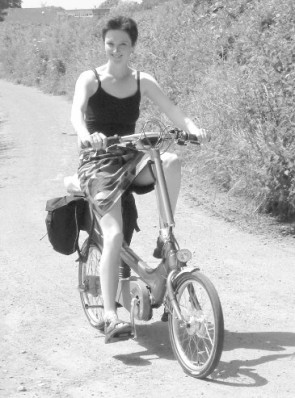

The high handlebars are very typical of a Dutch roadster. The batteries are effectively hidden

Generally,road speed is not high.We averaged 12.4mph on a hilly route,which is a little slower than the Lafree,but identical to the Sparta Ion.It’s worth pointing out that the Lafree’s crank motor could be tweaked with higher gearing to give ‘longer legs’,or with lower gearing to improve hill-climbing – all for the cost of a little sprocket.Although technically illegal,higher gearing only increased the average speed by 1mph or so,but gave nicer ratios for pressing on,with or without power,particularly useful with a following wind.On the new model,this sort of fine-tuning isn’t possible,or at least it is,but a change of rear sprocket will only increase the gearing for your legs , because the motor drives the front wheel.So in terms of adaptability,the old bike was much better.

With the slight motor drag,the extra weight,and that sharp cut-off at 15mph,journey times will not bring forth oohs and aahs from your friends.Our largely flat,but somewhat exposed 10-mile ‘commuter’ circuit took 41 1 / 2 minutes (an average of 13.2mph),where 35 to 40 minutes would be the norm for a good electric bike,and even a decent non-assisted folder (see Moulton in this issue) can better 40 minutes.

Tyres look jolly good.They’re designed in Holland (or so it says on the sidewall) and made by CSR,which turns out to be our old friend Cheng Shin Rubber,manufacturer of almost every bicycle tyre on the planet.Being generally slick,but with a handful of groovylooking swept back grooves,they look distinctly sporty.In practice,it’s hard to tell how effective they are,because the motor drag limits the rolldown speed to 10.6mph,which is bad news for a big-wheeled bike like this.Anyway,the tyres certainly look the part.

Brakes are a bit of a mixture.The front V-brakes are a bit too powerful,easily achieving a stable,safe emergency stop of .68G.It’s easy to go a bit too far – we saw .72G,but at this point the rear wheel is starting to lift off. In marked contrast,the Nexus roller brake at the back is a bit feeble,scraping up to .2G a long way from locking the wheel.From experience,we know these brakes improve a bit when properly ‘run in’,and they can easily go on to outlive the bike,but they’re not really strong enough to control a heavy trailer,and can overheat on long descents.

The ride is a bit hard,certainly compared to the Sparta Ion.Like the 1960s Moulton, the Twist front suspension uses a single spring hidden within the fork tube,but it doesn’t work half as well,being stiff and unresponsive,with limited travel.

…Giant claim up to 100 miles… 40 miles seems a safe overall figure…

Hill Climbing

The old Lafree was a slow but able hill climber, chugging up more or less anything.Putting the motor in the front wheel is easier and cheaper for Giant,but it does put a limit on hill climbing,because as road speed falls,the motor begins to lose interest.This makes it a bit difficult to put a figure on the maximum gradient,because so much depends on the strength of the rider. We found gradients of 1:8 relatively easy,and even managed a restart on 1:6,but that’s about it. This sort of thing is only possible because of the low first gear – something the cheaper Twist 2.0 won’t have.

As for going down the other side,the Twist does technically have regenerative braking, but it’s extremely limited.You have to find and press a rather fiddly button to make it work, it only cuts in above 10mph,and when it does,it’s so weak as to be almost unnoticeable. Only on a couple of long fast descents did we feel any retardation,and then only for a few seconds. Our bike may have been faulty,but the regen braking is too weak to be of any practical use. Disappointing is the word.

Range

Giant claims a range of up to 100 miles for the Twist,but that’s on the flat,with no headwind,using the lowest ‘Eco’ power setting,and subject to almost a page of caveats.No doubt this is possible in ideal conditions, but for the averagely tubby Westerner,in late for work mode,on a miserable cold and wet January morning,forget it.To be fair,Giant is realistic about this worst case scenario,claiming a more modest 25 to 38 miles.Using the highest ‘Power’ setting in near freezing weather and with some icy headwinds gave a figure of 18.5 miles per battery,which is more or less in line with expectations. Further trips yielded 20 to 23 miles per battery,so 40 seems a safe overall figure.

The battery capacity is indicated by a line of five LEDs.The first two are pretty inaccurate,popping off at the first sniff of a gradient,and very often coming back down the other side (no,that’s not regen).Then there’s a long pause until somewhere around 10 miles,when light three goes out.Once light four has gone (15 miles or so),power starts to sag,warning you that the final act is not far off.Normally, a slightly vague gauge would be a problem,but with two batteries,you simply flick a switch…assuming,of course,that you charged the correct battery last night.This reminds us of a friend with a Jaguar 420G who took out a second mortgage to fill both tanks,drove until the first tank was exhausted, pressed the button…and found the second fuel pump wasn’t working.There’s a moral there somewhere.

Is it fair to test the Twist only in ‘Power’ mode? We think so.We’ve used the setting that gives the closest approximation to the performance of the old Lafree in the same conditions.Ridden hard,that would do about 20 miles,or a fair bit more with care,but with twin batteries,the new Twist beats it hands down in terms of range.It’s actually rather less economic,drinking 15 watt/hours of juice per mile,against 10 or so for the old bike, but that was – to be fair – exceptionally frugal.In any event the Twist has so much more battery available,economy isn’t a major issue.

Charging

Things fall down badly here,but it’s a new design,so Giant should be able to sort things out before they hit the shops.The batteries are hung either side of a special rack,and they’re neatly encased by a pair of equally special panniers.The idea is that you turn a key with one hand,open the pannier and reach in with the other hand,then swing the battery down,unfurl a handle and lift it free.Ha! The man from Giant couldn’t do it,and we couldn’t either. In the end,two of us removed the panniers, and after quite a bit of head-scratching and pushing and shoving,we had a battery out.Once it’s out,be very very careful. On the front face,and serving no particular engineering purpose,are four plastic plates,as sharp as razor blades. We received a nasty cut on Day One,and a guest was bitten the following day…

Unfortunately,the charge socket is under the battery handle, and the handle cannot be folded down until the battery is most of the way out.Catch 22:you can’t grab the batteries without removing the panniers,but if you remove the panniers,the battery has to come right out or it will fall on the ground.And when you pick it up,you cut a finger on the nasty projections.Some people simply will not be able

…The battery problem sounds suspiciously like Computer Aided Design disease…

to charge the Twist batteries unless this lot is sorted out.Something else you could never predict is that with two identical batteries, your typically muddle-headed A to B tester soon forgets which is charged and which isn’t. ‘A’ and ‘B’ labels would help a bit here,and give us some free publicity.

Once the battery’s out,the charging process is straightforward.At 1.2kg and 20cm x 10cm x 5cm,the charger is rather large,but reasonably quick.It runs at full power for two hours,bringing the battery to 70% capacity,then at a slower rate for another hour and three-quarters,before shutting down – exactly the same as the old model.You can leave the battery connected for the rest of the night if you wish,but no longer,says the manual. Unfortunately,the batteries have to be charged independently,so a commuter travelling more than twenty miles a day will need to get the body armour back on and brave another battery swap late in the evening,leaving the second battery on charge overnight.

The whole battery problem sounds suspiciously like Computer Aided Design disease. In this sadly all too common scenario,some bright,spotty-faced young thing creates a wonderful 3D object d’art on a computer screen,but no-one actually finds out whether it bites until tens of thousands of dollars have been spent on tooling and it arrives at Manor Road,Dorchester.Amazing. Yes,the old Lafree battery was an ergonomic delight to whip in and out.Sometimes we used to do it just for the hell of it .

Accessories

Good and bad news here.Starting with the very minor things,the bell is superb wonderful clear note,nice action,clever bit of design.The nice big centre stand looks a great advance on the puny side-stand fitted to the old Lafree,but it (literally) falls down in practice by not going far enough ‘over-centre’,leaving the bike vulnerable to rolling forward off the stand.This tends to happen as you finally and triumphantly wrestle a battery out. Gravity being what it is,removing one battery causes the rear of the bike to bob gently up, and if it’s on a slight slope,the stand will fold slowly away,leaving you open mouthed as the S S Twist launches gently forward to roll away into the flowerbed.A change to the stand geometry will cure the problem,and it needs to be done.

The lights are good,but again there are minor niggles.The rear light is a batterypowered LED,with a top-mounted switch that can be easily prodded on with a gloved hand.Unlike the Lafree Comfort,this is not automatic,and ours failed within a week.This could happen to any bike,of course,but for £1,400 you rightly expect the best.

The Spanning a Radius halogen light is controlled from a fiddly little push button on the handlebar ‘dashboard’. This probably looked fine spinning around in 3D too,but with gloved hands,riding on a dark country lane,it’s all too easy to turn the light off as you grope for something else.To get it back on,you have to steer your finger by the little constellation of LEDS and make a stab in the right place.If you’re blinded by car lights,this is near impossible,and quite a dangerous operation.The headlight will also go off if the systems shut down for any reason.This happened to us a couple of times pulling out of junctions, when the motor stuttered then returned,but the light stayed out.The same is true if you change ‘tanks’ on the move – the motor only goes off for a second,but the light stays off until you hit that little switch.Annoying,and potentially dangerous.

In most respects,the light is an improvement on the old dynamo system.Drawing power from the traction battery means it’s always available,so there are no worries when stationary and turning right.Even if both the batteries are flat,Giant reckons there is enough power left to run the light for ten hours.A good system,but the switch needs a rethink.It would be safer to put a nice big chunky light switch safely out of reach (see Sparta).So mixed fortunes here – the new lights are better than the cheapy dynamo lights fitted to the old Lite model,but not as good as the wonderful Busch & Müller automatic lights on the Lafree Comfort.

Elsewhere,it’s nice to see a pump (neatly hidden under the panniers),the wheel lock is great,and the chainguard is functional,but a bit fiddly to remove.The panniers themselves are futuristic sculpted affairs,but as Jane immediately points out,compared to the capacious Bling Bling panniers that have been fixtures on her Lafree since we tested them in A to B54 ,they are too small,and fiddly to use.A4 paperwork fits neatly inside,but you have to scrunch the papers through a letter box slot to get them in.Stylish maybe,but the capacity just isn’t there,and the unusual rack means that normal rigid-backed panniers,such as Carradice or Ortleib,will not fit.If this bike is going to be truly practical for nipping to the shops or commuting,a rethink is needed.

Conclusion

That’s our technical analysis,but most cyclists aren’t interested in whether the battery is a Nimby or a Lion;they just want something that will work and keep working at a reasonable cost.There’s no escaping that the Twist 1.0 will be expensive to run.A £1,400 purchase price,plus an estimated £300 per replacement battery (don’t forget there are two) gives a scary running cost of 12.1p per mile.

We rounded up four Lafree owners to try the new model – would they swap their tired old machine for this shiny new one? The rigid frame and build quality of the bike were much admired,as was the handling,but it was also described as ‘slow’ (this,of course,is somewhat illusory),heavy (again,not entirely fair),and boring.Some came round to it,but grumbles persisted about the small panniers,and problems with upgrading them,the pedals being too far back,the lack of a handle to lift the bike onto the stand,and the price,which was considered way over the top for a Chinese machine,albeit a good one.The fact is,the Twist is closely related to the Giant Suede,but it costs more than twice as much.

It should be a matter of some concern to Giant that only one was willing to swap his old model for £1,400 worth of shiny new bicycle,and he was very unsure.Of course,in some respects,a focus group in love with the old model is bound to be biased from the start.Giant is delighted with the bike’s reception in The Netherlands,where 5,000 are reported to have been sold since November.

The new Twist has some good features,and one or two excellent ones,like the 40mile range,which is more or less unbeatable.But we have a hunch buyers will opt for the 2.0 model instead.This has most of the same features,but is fitted with a pair of (arguably more reliable) NiMH batteries instead of lightweight Li-ion.This means a more reasonable £1,100 for the bike,with running costs of around 8.4p per mile.

Specification

Giant Twist 1.0 £1,400. Weight bicycle 24.9kg batteries 5.2kg total 30.1kg (66lbs). Gears Shimano Nexus. Ratios29″-89″. Wheelbase116cm. BatteryLi-ion. Capacity2 x 270Wh Range40 milesFull charge 7hrs 30min . Fuel Consumption overall 13.5-16.8 Wh/mile Running Costs 12.1p per mile. Manufacturer Giant Bicycles UK distributor Giant UK Ltd tel 0115 977 5900 mail info@giant-uk.demon.co.uk

A to B 58 – Feb 2007

![]()

Nothing stands still,especially in the world of electric bikes.Not so long ago,buyers who couldn’t afford the £850+ for a basic Giant Lafree were faced with a huge choice of cheaper alternatives,all of them heavy,slow and relatively crude. That looks like changing,with a new breed of bikes in the £500-£600 range,of which Giant’s own Suede is the most obvious example.And these cheaper bikes are getting better:the Suede is expected to be relaunched in 2007 with a freewheel in the motor, the lack of which was one of our biggest criticisms. None are as sophisticated as the purely pedelec Lafree,but the new generation all make use of Nickel-Metal Hydride (NiMH) batteries,which weigh about half as much as traditional lead-acids, and they are finally starting to come down in price as production volumes increase. The Powacycle Windsor is one such,and at £499 appears to tick most of the right boxes.It’s got a NiMH battery,aluminium step-through frame,smart black wheel rims,Vbrakes and a sturdy rack. And it weighs 23.7kg – slightly less than claimed,and lighter than almost anything except the basic Lafree. There’s been a fairly obvious attempt to give it a Lafree sort of look,and in a chunky,less elegant way, they’ve succeeded. If there’s a drawback,it’s that the Windsor’s battery is a relatively puny 192 watt/hours (the Ezee range,for example,offer 324 watt/hours) so it won’t be burning any tarmac.

Nothing stands still,especially in the world of electric bikes.Not so long ago,buyers who couldn’t afford the £850+ for a basic Giant Lafree were faced with a huge choice of cheaper alternatives,all of them heavy,slow and relatively crude. That looks like changing,with a new breed of bikes in the £500-£600 range,of which Giant’s own Suede is the most obvious example.And these cheaper bikes are getting better:the Suede is expected to be relaunched in 2007 with a freewheel in the motor, the lack of which was one of our biggest criticisms. None are as sophisticated as the purely pedelec Lafree,but the new generation all make use of Nickel-Metal Hydride (NiMH) batteries,which weigh about half as much as traditional lead-acids, and they are finally starting to come down in price as production volumes increase. The Powacycle Windsor is one such,and at £499 appears to tick most of the right boxes.It’s got a NiMH battery,aluminium step-through frame,smart black wheel rims,Vbrakes and a sturdy rack. And it weighs 23.7kg – slightly less than claimed,and lighter than almost anything except the basic Lafree. There’s been a fairly obvious attempt to give it a Lafree sort of look,and in a chunky,less elegant way, they’ve succeeded. If there’s a drawback,it’s that the Windsor’s battery is a relatively puny 192 watt/hours (the Ezee range,for example,offer 324 watt/hours) so it won’t be burning any tarmac.

Both of these machines look like stylish, sophisticated urban transport tools, and for some people, that’s more than enough, whether they work or not. The A-bike, in particular, is cheap (£199) and sufficiently compact to be artfully posed as a loft-living object d’art. As a folded package it’s as neat and homogeneous as a folded Brompton. Unfolded, it’s rather less successful, appearing somewhat spindly and frail. It also looks like a bike without any wheels, because where you expect to see wheels, there are two six- inch rubber diskettes. Yup, those are your wheels.

Both of these machines look like stylish, sophisticated urban transport tools, and for some people, that’s more than enough, whether they work or not. The A-bike, in particular, is cheap (£199) and sufficiently compact to be artfully posed as a loft-living object d’art. As a folded package it’s as neat and homogeneous as a folded Brompton. Unfolded, it’s rather less successful, appearing somewhat spindly and frail. It also looks like a bike without any wheels, because where you expect to see wheels, there are two six- inch rubber diskettes. Yup, those are your wheels.

If anything, the Genius is even easier to fold. The scissor-style frame is held in either the up or down position by a single metal rod resting on the rear frame. When you’re riding, this takes your weight. Lift the bike by its central carry-handle and the rod prevents the frame closing up until it’s pushed towards the chunky saddle stem. With the rod out of engagement, a lift on the handle brings the frame and wheels together. Finally, a quick-release lowers the saddle,and you lift a pair of buttons like trumpet valves to fold the bars down. Time is broadly similar to the A-bike,but at 14.1kg (31lb) the resulting lump is very nearly three times the weight.

If anything, the Genius is even easier to fold. The scissor-style frame is held in either the up or down position by a single metal rod resting on the rear frame. When you’re riding, this takes your weight. Lift the bike by its central carry-handle and the rod prevents the frame closing up until it’s pushed towards the chunky saddle stem. With the rod out of engagement, a lift on the handle brings the frame and wheels together. Finally, a quick-release lowers the saddle,and you lift a pair of buttons like trumpet valves to fold the bars down. Time is broadly similar to the A-bike,but at 14.1kg (31lb) the resulting lump is very nearly three times the weight.

Why would anyone want to pay much, much more for a lightweight folding bike? We get asked this quite often by big burly types.There are two primary markets,the obvious one being smaller people looking for something light and easy to hoik up into a car boot for leisure rides.The other is much more interesting stuff,and goes right to the heart of what we’re about and what we believe,because a lightweight folding bike takes the user into a new world of seamless, effortless integrated transport. Once you’ve ridden one of these bikes on city streets,hopping on and off, and vaulting onto trams and trains, you will be hooked. In the leisure market, a kilogramme here or there is of little consequence, but if your folding bike is your primary means of transport, you too will be prepared to pay big money to make it as light and convenient as possible. These are the lightest bikes around,if we omit custom Bike Fridays and esoteric folders like the Sinclair A-bike.We’ve tested both the S2L-X and Mu before in slightly different form.The Mu replaces the lightweight Helios SL we tried in August 2004 ( A to B43 ), we had a brief go on the Brompton S2L-X in April 2005 ( A to B47 ) and have since built our own super-lightweight derivative ( A to B49 ). Here we test them together for the first time. Is there are a clear best buy?

Why would anyone want to pay much, much more for a lightweight folding bike? We get asked this quite often by big burly types.There are two primary markets,the obvious one being smaller people looking for something light and easy to hoik up into a car boot for leisure rides.The other is much more interesting stuff,and goes right to the heart of what we’re about and what we believe,because a lightweight folding bike takes the user into a new world of seamless, effortless integrated transport. Once you’ve ridden one of these bikes on city streets,hopping on and off, and vaulting onto trams and trains, you will be hooked. In the leisure market, a kilogramme here or there is of little consequence, but if your folding bike is your primary means of transport, you too will be prepared to pay big money to make it as light and convenient as possible. These are the lightest bikes around,if we omit custom Bike Fridays and esoteric folders like the Sinclair A-bike.We’ve tested both the S2L-X and Mu before in slightly different form.The Mu replaces the lightweight Helios SL we tried in August 2004 ( A to B43 ), we had a brief go on the Brompton S2L-X in April 2005 ( A to B47 ) and have since built our own super-lightweight derivative ( A to B49 ). Here we test them together for the first time. Is there are a clear best buy? On the Road

On the Road

Decisions, decisions, decisions… You know how it is, life’s treated you well, and you’ve settled on a Roller for best, and a Bentley for , you know, just pottering. But where do you find a matching folding bike? And what criteria do you use? Andrew Hague takes up the story, while Laila models the bikes…

Decisions, decisions, decisions… You know how it is, life’s treated you well, and you’ve settled on a Roller for best, and a Bentley for , you know, just pottering. But where do you find a matching folding bike? And what criteria do you use? Andrew Hague takes up the story, while Laila models the bikes…

And then Brompton produced the titanium bikes, and the urge to upgrade got the better of me. I bought an S2L-X.This much lighter machine simply cried out to be carried, and as I couldn’t buy a rucksack to carry the Brompton, I decided to make one myself instead.

And then Brompton produced the titanium bikes, and the urge to upgrade got the better of me. I bought an S2L-X.This much lighter machine simply cried out to be carried, and as I couldn’t buy a rucksack to carry the Brompton, I decided to make one myself instead.

A quick flick through our transitory bike collection revealed that the SP Luggage Post will fit most small-wheeled bikes, from Moultons and Micros to the Airframe, plus the majority of full-size bikes, provided they have enough clearance between the rack and saddle.The only real problem is that a suspension seat-post will probably get in the way. An advantage with smallwheelers is that the block can be fitted very low down, putting the load rather lower than it would be on a big bike, helping to keep things stable. On some bikes, the Luggage Post can be lowered until some of the weight is carried on the rack – a good idea if you are intending to carry a lot of weight (Brompton suggest a maximum of 10kg for the block itself, but we’d suggest keeping below 8kg). On the Brompton, folding is more or less unaffected. Loosen the quick-release on the Luggage Post, swing it forward, and you end up with a folded package a little taller than normal. In 30 seconds or so, the post can be removed and refitted upside down, leaving the bike more or less as compact as any other.The weight penalty of 480g, complete with fittings, is a modest price to pay for such versatility.

A quick flick through our transitory bike collection revealed that the SP Luggage Post will fit most small-wheeled bikes, from Moultons and Micros to the Airframe, plus the majority of full-size bikes, provided they have enough clearance between the rack and saddle.The only real problem is that a suspension seat-post will probably get in the way. An advantage with smallwheelers is that the block can be fitted very low down, putting the load rather lower than it would be on a big bike, helping to keep things stable. On some bikes, the Luggage Post can be lowered until some of the weight is carried on the rack – a good idea if you are intending to carry a lot of weight (Brompton suggest a maximum of 10kg for the block itself, but we’d suggest keeping below 8kg). On the Brompton, folding is more or less unaffected. Loosen the quick-release on the Luggage Post, swing it forward, and you end up with a folded package a little taller than normal. In 30 seconds or so, the post can be removed and refitted upside down, leaving the bike more or less as compact as any other.The weight penalty of 480g, complete with fittings, is a modest price to pay for such versatility.

‘It goes like the wind’: my initial somewhat subjective assessment of the new Birdy as I cycled across Westminster Bridge in London three days before Christmas last year. Would I feel as happy after the honeymoon period? The new Birdy was announced last September at various German cycling shows and a pre-production example was on display at the London Cycle Show in October. So what’s changed from the old model? The most obvious difference is a completely new frame. Instead of the angular rather unconventional look, the new frame is two pieces of shaped aluminium welded together. Riese and Müller, the manufacturers, call it a ‘monocoque frame’ welded together using ‘robotic technology’. The lines are much cleaner and the overall look much more twentyfirst century than the old model. R & M claim that the new bike is marginally lighter (140g less) and has a stiffer frame.

‘It goes like the wind’: my initial somewhat subjective assessment of the new Birdy as I cycled across Westminster Bridge in London three days before Christmas last year. Would I feel as happy after the honeymoon period? The new Birdy was announced last September at various German cycling shows and a pre-production example was on display at the London Cycle Show in October. So what’s changed from the old model? The most obvious difference is a completely new frame. Instead of the angular rather unconventional look, the new frame is two pieces of shaped aluminium welded together. Riese and Müller, the manufacturers, call it a ‘monocoque frame’ welded together using ‘robotic technology’. The lines are much cleaner and the overall look much more twentyfirst century than the old model. R & M claim that the new bike is marginally lighter (140g less) and has a stiffer frame.

One wonders what goes on in the boardrooms of folding bike manufacturers. Are board members instructed never to mention the ‘B’ word? Or do they ritually stick pins in plasticine models of the Brentford Folder? The fact is – and we might as well get this over with – the Brompton is more or less unassailable in terms of practicality, ride and foldability.We’ve never seen a bike come close: a few 20-inch big wheelers are faster (not all though), a handful of machines have a rudimentary luggage carrying system, and some fold quite well, but the Brompton scores at least 8/10 in all these areas, so it can’t be beaten. Not yet, anyway. To successfully compete against the wunder-fahrrad, you need a machine that is significantly cheaper (certain Dahons and others), faster (Bike Friday and Airnimal), or that exploit the Brompton’s primary weakness – its limited gear range.

One wonders what goes on in the boardrooms of folding bike manufacturers. Are board members instructed never to mention the ‘B’ word? Or do they ritually stick pins in plasticine models of the Brentford Folder? The fact is – and we might as well get this over with – the Brompton is more or less unassailable in terms of practicality, ride and foldability.We’ve never seen a bike come close: a few 20-inch big wheelers are faster (not all though), a handful of machines have a rudimentary luggage carrying system, and some fold quite well, but the Brompton scores at least 8/10 in all these areas, so it can’t be beaten. Not yet, anyway. To successfully compete against the wunder-fahrrad, you need a machine that is significantly cheaper (certain Dahons and others), faster (Bike Friday and Airnimal), or that exploit the Brompton’s primary weakness – its limited gear range.

Cutting edge stuff! Whatever your preference in alternative transport, this issue will show you something entirely new. Folding bike? Follow our lightweight Brompton project – 10.9kg in 1997 and 9.5kg today. Electric bike? We can offer a range of 35 miles from a Lithium-ion battery… Gears? Professor Pivot investigates a practical fully automatic gearbox… Recumbents? Giant’s new Revive Spirit is stashed with technology.

Cutting edge stuff! Whatever your preference in alternative transport, this issue will show you something entirely new. Folding bike? Follow our lightweight Brompton project – 10.9kg in 1997 and 9.5kg today. Electric bike? We can offer a range of 35 miles from a Lithium-ion battery… Gears? Professor Pivot investigates a practical fully automatic gearbox… Recumbents? Giant’s new Revive Spirit is stashed with technology.

If you think about it, the quality of a child’s bike is really important. If a child grows up with a heavy, impractical bicycle, he or she starts life with the impression that bicycles are heavy impractical machines.The evidence from the current generation is that apart from dabbling with BMX, the vast majority stop riding bicycles just as soon as they can, and most never return. Rather disturbingly, there’s growing evidence that many in Alexander’s generation will never learn to ride at all.

If you think about it, the quality of a child’s bike is really important. If a child grows up with a heavy, impractical bicycle, he or she starts life with the impression that bicycles are heavy impractical machines.The evidence from the current generation is that apart from dabbling with BMX, the vast majority stop riding bicycles just as soon as they can, and most never return. Rather disturbingly, there’s growing evidence that many in Alexander’s generation will never learn to ride at all.

The Giant Revive, it’s fair to say, has been a long time coming.We first heard whispers of a commercially-produced semi-recumbent bicycle some years ago, and eventually saw one in the summer of 2002.The non-assisted versions went on sale the following spring, the electric variant finally arriving in the summer of 2005.

The Giant Revive, it’s fair to say, has been a long time coming.We first heard whispers of a commercially-produced semi-recumbent bicycle some years ago, and eventually saw one in the summer of 2002.The non-assisted versions went on sale the following spring, the electric variant finally arriving in the summer of 2005. A brief recap. In recumbent terms, the Revive might be described as a short wheelbase semi-recumbent.The frame is alloy throughout, with various bits hung from a solid- looking main tube that drops down from the steering head area, giving a usefully low step-thru, then sweeps back and up over the rear wheel.The wheel is fixed to another frame member that pivots just ahead of the crank and is supported by a spring/damper unit under the seat tube, which swings sharply upwards from the main frame.Wheels are 406mm (20-inch).

A brief recap. In recumbent terms, the Revive might be described as a short wheelbase semi-recumbent.The frame is alloy throughout, with various bits hung from a solid- looking main tube that drops down from the steering head area, giving a usefully low step-thru, then sweeps back and up over the rear wheel.The wheel is fixed to another frame member that pivots just ahead of the crank and is supported by a spring/damper unit under the seat tube, which swings sharply upwards from the main frame.Wheels are 406mm (20-inch). Less satisfactory is the weight, the price and the slightly awkward pedalling position. In its short life, the Revive has been produced in a number of versions, but only two models are currently on sale in the UK both with hub gears – Nexus 7-speed on the Revive DX N7 (£675), and Nexus 8-speed on the more luxurious LXC N8 (£875). Giant is a bit coy about weight, but reports suggest these non-assisted machines weigh at least 19kg (42lb), which compares rather badly with similar conventional bikes.With low drag and high weight, bikes of this kind tend to see more extremes of speed than a traditional bicycle – heart- stopping descents and painfully slow climbs. And that’s where the power-assisted Spirit comes in, because a little assistance goes a long way to even out your progress.

Less satisfactory is the weight, the price and the slightly awkward pedalling position. In its short life, the Revive has been produced in a number of versions, but only two models are currently on sale in the UK both with hub gears – Nexus 7-speed on the Revive DX N7 (£675), and Nexus 8-speed on the more luxurious LXC N8 (£875). Giant is a bit coy about weight, but reports suggest these non-assisted machines weigh at least 19kg (42lb), which compares rather badly with similar conventional bikes.With low drag and high weight, bikes of this kind tend to see more extremes of speed than a traditional bicycle – heart- stopping descents and painfully slow climbs. And that’s where the power-assisted Spirit comes in, because a little assistance goes a long way to even out your progress. At £1,499, the Spirit is the most expensive electric bike in the UK, by several hundred pounds. It’s also the most sophisticated: lithium-ion battery, integral trip computer, automatic halogen light and many other cumfy luxuries. Strangely enough, given the quality of the equipment, the Spirit is fitted with one of the world’s most basic hub gears; Shimano’s three-speed Nexus.We express surprise because this hub is also available in Auto-D form, and an automatic hub would seem ideal for a laid- back flagship like the Spirit. And this year, Shimano has introduced something called Di2 cyber Nexus, bringing together its generally well considered eight-speed hub with a front hub-powered computer, auto shift mechanism, auto suspension, auto lights, and… well, you get the idea.

At £1,499, the Spirit is the most expensive electric bike in the UK, by several hundred pounds. It’s also the most sophisticated: lithium-ion battery, integral trip computer, automatic halogen light and many other cumfy luxuries. Strangely enough, given the quality of the equipment, the Spirit is fitted with one of the world’s most basic hub gears; Shimano’s three-speed Nexus.We express surprise because this hub is also available in Auto-D form, and an automatic hub would seem ideal for a laid- back flagship like the Spirit. And this year, Shimano has introduced something called Di2 cyber Nexus, bringing together its generally well considered eight-speed hub with a front hub-powered computer, auto shift mechanism, auto suspension, auto lights, and… well, you get the idea.

Range on full power is so- so.There are three capacity lights: On our ‘mountain course’, the first popped off at four miles and the second at six miles, which almost caused us to abort the test. In practice, the gauge is a bit hit- and-miss, because we soon had two lights on again. Four miles on we were back with one, at 14 miles it began to flash, and the end came abruptly at 16.2 miles. Average speed was 13.7mph – quite low by modern electric bike standards, particularly considering the rapid descents. In flat country, we managed 17.4 miles at 14mph, which is even more disappointing.

Range on full power is so- so.There are three capacity lights: On our ‘mountain course’, the first popped off at four miles and the second at six miles, which almost caused us to abort the test. In practice, the gauge is a bit hit- and-miss, because we soon had two lights on again. Four miles on we were back with one, at 14 miles it began to flash, and the end came abruptly at 16.2 miles. Average speed was 13.7mph – quite low by modern electric bike standards, particularly considering the rapid descents. In flat country, we managed 17.4 miles at 14mph, which is even more disappointing.

Once upon a time, not so very long ago,if you lived beside a British trunk road your life would be a nightmare of congestion, pollution and constant danger. As the years passed, the nightmare spread; first to ‘A’ class roads, then ‘B’ roads (remember when you could cycle on those sweeping rural highways?), and finally to unclassified roads in all but the most remote corners of these islands.

Once upon a time, not so very long ago,if you lived beside a British trunk road your life would be a nightmare of congestion, pollution and constant danger. As the years passed, the nightmare spread; first to ‘A’ class roads, then ‘B’ roads (remember when you could cycle on those sweeping rural highways?), and finally to unclassified roads in all but the most remote corners of these islands. Not to put too fine a point on it, this is utter nonsense. According to the Department for Transport’s ‘Road Safety Good Practice Guide’, urban residential roads account for nearly 40% of all crashes (‘accidents’, according to DfT) and a high proportion of the casualties are children.The answer, according to recommendation 4.67, is that: ‘On residential access roads drivers need to be given visual cues that indicate strongly that this road space is part of the environment where people live, walk, talk and play.’

Not to put too fine a point on it, this is utter nonsense. According to the Department for Transport’s ‘Road Safety Good Practice Guide’, urban residential roads account for nearly 40% of all crashes (‘accidents’, according to DfT) and a high proportion of the casualties are children.The answer, according to recommendation 4.67, is that: ‘On residential access roads drivers need to be given visual cues that indicate strongly that this road space is part of the environment where people live, walk, talk and play.’