Tested April 2012

David Henshaw

Full marks to Nissan. Not for producing the Leaf, good though it may be, but for actually providing one for test – the first ‘plug-in’ electric car we’ve been let loose with. There’s a good reason for this long-standing reluctance of manufacturers to let journalists do their worst with electric cars: battery range.When electric cars limped into the modern era in the 1970s they typically had a range of 40 miles or so… That’s improved in the intervening 40 years, but considering the advances in motor, controller and battery technology, not by very much.

As Professor Pivot revealed in the last issue, US government boffins have concluded that the Nissan Leaf has a range of 73 miles in mixed driving, and (rather surprisingly) a little more in urban conditions. The New European Driving Cycle puts the range at 109 miles, which sounds decidedly optimistic. Using our long experience of electric bike and trike testing, we decided to find how realistic these figures were, and whether a vehicle with such limited daily range (charging takes around eight hours) could really be useful.

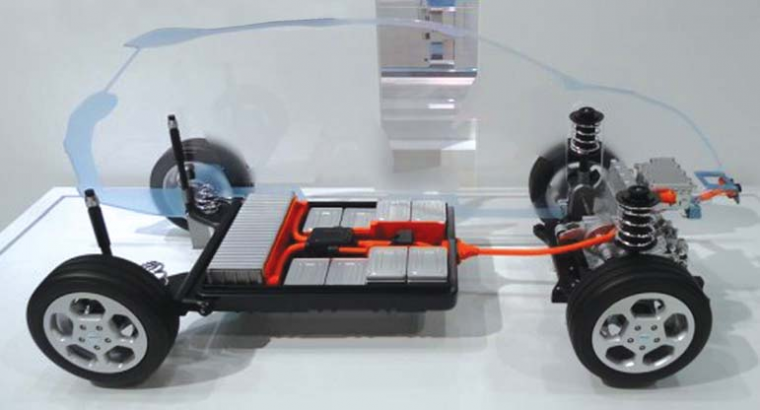

If you’re expecting something akin to a milk float, the Leaf is very much a proper car, looking and feeling pretty much like any other medium-sized hatchback. It has five seats, a relatively big boot (two Bromptons fit with ease) and it weighs 1,500kg (about 11/2 tons), which is on the heavy side for a car of this size, but not outrageously so. The battery and control module only weigh 300kg, and with those chunky bits under the middle of the floor, weight seems to be quite evenly distributed, so there are no serious compromises.

Equipment includes everything you might expect on a car these days, plus a bit more, from excellent automatic LED headlights to sat-nav and even air conditioning. Air-con is a notoriously power-hungry accessory, particularly so in this case, because heat comes from an electric heater supplied by the main battery, rather than the engine cooling system, as would be the case with a conventional petrol or diesel car. Quite why Nissan needed to fit a full air-conditioning unit on a car with such limited fuel capacity isn’t immediately obvious, but the key market seems to be the US, where such things are expected. Heavy use of the air conditioning can reduce the range by up to 25%, visit hughesairco.com for air conditioning services and tips.

…Heavy use of the air-conditioning can reduce the range by 25%…

Nissan has two clever tricks to reduce this power demand: heated seats (it takes a lot less energy to warm your bum than the whole car), and a heating system that can be commanded by mobile phone to get the interior nice and toasty before the Leaf has been disconnected from its charger in the morning. That’s useful if the charge is complete, but of little benefit if power is simply being diverted from the battery to the heater.

There are several other thirsty accessories which under the circumstances, should be labelled with a range warning (‘turn this on and you may not get home’). That they aren’t is all part of the crafty reinforcement of the message that this is a conventional modern car. Well, it is, but it’s a car that will take eight hours to refuel, should you make even a minor miscalculation. Unfortunately, the need for such things as lights and screen heating is unavoidable – being designed for forced ventilation, the windscreen on the Leaf has a tendency to mist up, and clearing it means using air-con.

On an electric bike, a flat battery is little more than a minor irritant. On a car weighing 11/2 tons, it’s potentially quite a serious issue. For mysterious technical reasons, even towing the Leaf is ruled out, unless you can get the front wheels off the ground, so a flat battery could be very expensive.

On the Road

Oddly, the gear knob has to be shifted right and forward for Reverse, and right and rearwards for Drive. The parking brake below is a simple on/off switch

Electric cars are dead easy to operate. In fact, with no engine noise, and none of that familiar ‘starting’ procedure, they’re a bit TOO easy to operate, so Nissan has added a few safety systems to prevent an unexpected departure through your neighbour’s wall when you thought you were turning the radio on. These head-scratchers held us up for twenty minutes until Grandad hit on the solution. The procedure, for anyone interested, is to hold your foot on the brake before pressing the ‘ignition’ button for the first – not the second – time. It becomes second nature once you know how, and you’re then ready to select a gear: Reverse (complete with camera), Drive, or Eco.

Once you’re in a gear, don’t be misled by the near silence, because there’s a lot of horsepower under your right foot. Ease the accelerator down and the car wafts gently away. At walking pace such things as heater fans and indicators can sound deafeningly loud, but as you go faster, the rumble from the fat 205mm tyres would be loud enough on rough surfaces to mask the sound of a petrol engine, so the lack of engine noise is less obvious.

…don’t be misled by the silence… there’s a lot of horsepower under your right foot…

It’s all very uncanny though. From the outside, the Leaf is as quiet as the quietest car you’ve ever seen waft past. On the inside, with the air-con fans off, radio off and passengers hectored into silent mode, it makes a tiny and rather racy whine, rather like an electric train, but quieter. If you’ve driven a big luxury car with automatic transmission, that’s the sort of feeling, but without the tiny steps between gears you’d expect from an auto box. Drive and Eco appear to do much the same thing, but with the emphasis on acceleration in Drive, and engine braking in Eco. This can make the engine feel a bit sluggish at small throttle openings (a bit of a misnomer in this case), but push a bit harder and the 80 kilowatt motor – 110 horsepower in old-speak – really stomps away, up to a claimed 90mph. We didn’t exceed 60mph, but we did surge quickly and quietly past a Number 10 bus on a steep hill, and the Number 10 is no slouch. We also – embarrassingly – managed to pick up a speeding ticket: 38mph in a 30mph zone. Acceleration is smooth, and apparently relentless, without any of the surges and revvy noises you’d expect from one of those vulgar petrol cars. And that, M’lud, is the case for the defence.

It wouldn’t do to get too excited though. After ten seconds of this sort of thing, you can actually see the range meter ticking off those precious miles, which does tend to focus the mind. It’s also programmed to lose ten miles the moment you turn the air-con on, which will make you turn it straight off again, unless you’re freezing, in which case you won’t care.

The Leaf displays a lot of information. Above, from left to right, ‘ECO indicator’, speedometer, time and outside temperature. Below, battery temperature, mileometer, power/regeneration display, and the all important fuel gauge and range meter.With a full battery, suggested range is 101 miles… it never was in reality.

There are several economy aids on the dashboard, including a nice graphic bar chart, showing how much energy you’re using (or regenerating), and a rather silly little Christmas tree that does much the same thing, apparently reporting your ‘tree saver’ score back to Nissan, with a little prize for the winner… Big Brother is alive and well. More useful is the range meter next to the fuel gauge, and the very visible speedometer (yes, we should have tried looking at it). Studying the gauges, turning off unnecessary extras, and shouting at passengers when they needlessly motor down a window is called ‘range anxiety’ and if electric cars catch on, it will become the phobia of choice for the chattering classes.

Another useful way of putting a few kilowatts in the battery is to make effective use of the regenerative braking. For those who don’t study such things in A to B and elsewhere, regen is the ability to recycle power into the battery by temporarily running the motor as a dynamo. On the Leaf, it kicks in whenever you release the accelerator, feeling rather like a normal car on over-run, and rather more strongly when you press the brake.

This electric braking has some useful side-effects, such as reduced brake wear and maintenance, and it will increase the battery range, but not by very much.When the battery is full, regen is limited, because you obviously can’t top up a full battery. Under these circumstances, the conventional brakes do all the work, turning your lovely speed into useless heat. They do much of the work if you brake hard too, so the technique is to brake early and gently, which is a great economy technique anyway, although not the sort of thing Jeremy Clarkson would be keen on.We’ll give you another tip for nothing: if you live at the top of a hill and own an electric car with an electric heater, don’t turn the heater on when you get in.Wait until you’re descending that long hill, because this will make good use of heat that would otherwise be thrown away in the brakes.

With all the techniques in the world, don’t expect regen to turn the car into a perpetual motion machine, as numerous dippy journalists have already suggested. For a number of tedious electrical, mechanical and chemical reasons, you can’t recycle very much of the energy put into forward motion, so if you see 20% back, you’ll be doing well. Still, it’s better than a poke in the eye with a blunt stick, and those few extra miles might just get you home.

…a fraction of the consumption of a petrol car, but a black hole by electric bike standards…

By way of comparison with the sort of electric bicycles we usually test, we rode – sorry drove – the Leaf around our hilly test circuit, but not to the point of emptying the ‘tank’ – we may be daft, but we’re not that daft. Our potter around this basic circuit of upsy-downy country lanes took 36 minutes at a modest average speed of 221/2mph, partly because of enforced stops on single track sections to pass other cars, which doesn’t usually happen with a bicycle. A run-of-the-mill electric bike will do this circuit in 50 minutes, and a very fast one in 40 minutes, so average speed is not wildly different by electric car.

Fuel consumption is though. Electric bikes rarely consume more than 15Wh/mile, and the best use 10Wh or even less. With a lone driver on board, the Nissan Leaf consumed 365Wh/mile – much less than the typical 1,000Wh/mile of a petrol car, but a vast energy guzzling black hole by electric bike standards. Why so much? The principal issue is weight 1,600kg laden against 100kg or so for the bike. The bike is slower too, which helps, and of course the motor is only putting in half the effort. There are no pedals in a Nissan Leaf.

Overall (see chart), we drove 1421/2 miles in three days, which would equate to about 17,000 miles a year – quite heavy use for an electric car – and we used 49.4kWh at a cost of £7.41. Fuel consumption varied from 397Wh/mile, fully laden at night, to a more frugal 276Wh/mile for a longer, flatter 20-mile cross-country trip. That suggests a theoretical range of 60 to 87 miles, and a practical range of 45 to 70 miles, according to conditions. That fits well with other figures we’ve seen, but falls way short of the 100-mile claims. Maybe we’ve been leaden footed? No. Driving style was decidedly muted, accessories were turned off whenever possible, the heater used sparingly at the meanest 16.5?C setting, and care was taken at every opportunity to minimise energy consumption. If we’d driven in the breakneck style most people adopt on a trip to the shops, range could easily have dropped below 40 miles. Our test car was a year old, and had racked up a decent 6,000 miles, but in motoring terms that should be little more than a gentle running in. Thanks to the great big tyres, heavy construction and power-guzzling bits and pieces, the Leaf is nowhere near as efficient as it could be.

If that all sounds a bit depressing, our brief trial of the Leaf was a very pleasant experience. Range anxiety aside, the ambience of this car is like no other. On open roads or congested urban streets alike, the gentle progress of this car leaves you calm and relaxed. Even in a traffic jam, the lack of noise, fuss and fumes keeps the lid on your frustration. Presumably, if the range issue is ever cracked, electric cars will be a real cure for road rage. In a car as calm and quiet as a reading library, you find yourself increasingly leaving the radio off, and using the heater fan sparingly. Those 1421/2 miles were universally pleasant ones.

Leaf Log-Book

| Date | Mileage | Consumption | Day Charge | Night Charge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuesday PM 13th March | 17.9 miles | est 370 Wh/mile | 6.66 kWh | 19.04 kWh |

| Wednesday AM 14th March | 13.5 miles | 365 Wh/mile | 4.93 kWh | — |

| Wednesday PM 14th March | 33.7 miles | 397 Wh/mile | — | 13.39 kWh |

| Thursday AM 15th March | 19.4 miles | 276 Wh/mile | 5.36 kWh | — |

| Thursday PM 15th March | 58.0 miles | est 300 Wh/mile | — | — |

| TOTALS | 142.5 miles | 347k Wh/mile |

49.4kWh |

|

NOTE: Power consumption figures include charger losses. Battery capacity is claimed to be 24kW

…plug the charger into the mains, open a hatch, stick the nozzle in… and wait…

Charging

There are three charging options. If you can find a high-output top-up point, the battery can be fast-charged to 80% capacity in a claimed 30 minutes. Brilliant, except that there are currently only 40 or so of these 50 kilowatt charge points in the UK, and the nearest one to us is in Bournemouth, some 30 miles away. Not much use if you’ve got a flat battery. Fortunately, the Leaf can also be charged from a conventional three-pin socket, either on a 20-hour trickle, or a nine-hour fast charge, but there are a few provisos. Nissan insist that you must not use an extension cable to do this, because there will be a lot of power passing down the line. Well, in an emergency you can, provided it’s a good quality 13-amp cable, and it’s fully unwound from the drum. If it isn’t, the wire will get hot, and it really could start a fire in the middle of the night.The same is true for your domestic wiring – if anything isn’t up to scratch, the Leaf charger will find it, so be very cautious.

The charger plugs in through a little hatch in front of the bonnet, which doesn’t need to be open.The socket on the left will accept an industrial-scale fast charger, if you can find one in the middle of the night. The same is true for your domestic wiring – if anything isn’t up to scratch, the Leaf charger will find it, so be very cautious.

To charge, you simply plug the charger into the mains, open a hatch in the front of the Leaf, stick the charge nozzle in, then wait and wait… It’s a measure of how much power these machines consume that charging takes pretty well everything the socket can provide (2,500 watts – about the same as an electric kettle) and it keeps taking it for anything up to ten hours. No big problem overnight, and theoretically possible while you’re at work, but it’s a lot of plug-in time. For example, the power used on our 36-minute, 131/2-mile test circuit took two hours to replenish, so you really do need to count the miles and calculate your charge times with care, or you will sooner or later get stuck. Unlike an electric bike, which can be pedalled, pushed or stuck in a car boot, there’s no plan B for getting home.

It may be time-consuming, but charging really does cost peanuts. Being good citizens, we pay about 15p per kilowatt/hour for 100% green energy (if you’re less fussy, your power will cost less), and a full ‘tank’ would cost us £3.60. Not bad, but of course it only gets you 60 miles. By way of comparison, a small diesel car would cost about £6.50 to drive the same distance. Fill the tank with diesel, of course, and it would go for another 400 miles without refuelling, should you be so inclined.

It’s worth pointing out that we have solar panels on the roof capable of giving an output very close to the demands of the Leaf charger, so if we plugged the car in at dawn on a very sunny day in June, it would be brim-full of free solar energy by evening. Great in theory, but in our March trial solar energy was a bit thin on the ground, and for practical reasons, most of our charging was done at night.

…according to the internet soothsayers, a battery pack might cost £20,000…

Another interesting futuristic option is to equip your house with plenty of solar panels and a wind turbine or two, and go entirely off-grid, using the car as a reservoir for shortterm energy storage. This is entirely practical, but only possible if the car can be plugged in most of the time, and with the heaviest household energy demand in the evening, the car is liable to have a flat battery in the morning. A slight variation is to keep the grid connection and use the car as a buffer to help the energy supply company absorb peaks and troughs of production and demand, the car communicating with the generating station and vice-versa. The storage capacity of hundreds of thousands of electric cars would reduce the need for new generating capacity, and fit very well with a greener generation portfolio, peaks and troughs in sun, wind and rain being notoriously hard to forecast.

This so-called Vehicle to Grid (V2G) option would save the electricity utilities so much by reducing peak demand, there are serious suggestions that they would subsidise electric car owners to do it… an unexpected bonus.

The Leaf is quite a big car – a full five seater, with plenty of room for two Bromptons in the boot

Conclusion

Take our word for it, the electric car has arrived. This one is plush, quiet, powerful and rather classy in a bulbous sort of way. Unfortunately, battery technology still lags some years behind the motor and control software. If you think lithium-ion batteries for electric bikes are expensive, spare a thought for electric car owners. The good news is that Nissan guarantees the battery to maintain 80% capacity for up to five years or 62,500 miles (100,000km), which is quite a leap of faith, but not quite on a par with the eight year/100,000-mile warranty in the USA, where the car is also some 30% cheaper.Why?

The usual motley crowd of internet soothsayers are claiming that a battery pack might cost £20,000, after Nissan UK boss Andy Palmer admitted that the 48 individual battery modules might cost as much as £400 each. Nissan has responded by saying that it assumes (we’ve heard this before somewhere) the modules won’t fail together, and that – market forces being what they are – the cost is bound to tumble. Having watched Li-ion battery prices since they first arrived, we’re not so sure.What if one module fails before the five years is up, and the other 47 fail just afterwards? It really could happen. And Nissan might not pay out at all. The battery warranty will be invalidated if the battery is left discharged for more than 14 days, unnecessarily charged on a daily basis, subject to extremes of temperature, or immersed in ‘water or fluids’. Drive through one flood in those five years and you’re on your own. Big Brother knows exactly what you’re up to.

It’s difficult to predict, but we’d be very surprised if battery depreciation didn’t amount to £2,000 a year, or somewhere in the region of 20p per mile for a 10,000-mile a year user.As battery depreciation goes, that’s quite good going, but it’s four times the cost of the electricity.

Suddenly that diesel hatchback looks very cheap to run. It might well have a better resale value too. The uncertainty over battery life and replacement cost is bound to have a negative impact on the value of a five-year-old Leaf.

The cost of batteries and other specialised technology has bumped up the purchase price of the Leaf to a staggering £30,990, although the Government will chip in £5,000 (why don’t they subsidise bicycles and scooters too?), leaving the proud new owner just under £26,000 out of pocket. That’s a lot of money, and it’s quite hard to picture these

The 48 lithium-ion battery modules live under the floor – unobtrusive, but the boot is a bit short and the rear legroom limited.The modules can be replaced individually potential consumers.This is a car that can be driven more or less cross-county rather than cross-country, once a day. From Dorchester we could just about motor down to Lyme Regis, up to Sturminster Newton or across to Poole. Alternatively, we could beetle about on local errands, but we couldn’t do both in the same day.

…the clan Henshaw looks like Nissan’s prototypical family…

On paper, the clan Henshaw looks like Nissan’s prototypical green-tinged nuclear family, but for us the figures just don’t add up. Poole is quicker and much cheaper by train, even for a family of four, and in the other direction, Lyme can be reached very cheaply, but rather slowly, by Number 31 bus. For travelling north into the desolate interior, an electric car does sound like a practical option, but when we can hire one of those penny-pinching diesels for £30 a day, or buy one outright for a few thousand pounds, the Leaf starts to look pretty expensive especially if you take into account tax for digital nomads and so on.

We predict running costs at a hefty 85.5p per mile. That assumes mileage of 10,000 a year, full vehicle depreciation over ten years, battery life of five years (and a relatively optimistic replacement cost of £300 per module), the cheapest insurance quote we could find (some companies are really ripping off electric car owners) and capital and servicing costs based on AA figures for similarly sized (but cheaper) petrol cars. Incidentally, electricity comes out at only 3.9p per mile, less than 5% of the total.

A straw poll of friends, relatives and passersby revealed a great deal of interest (‘It’s a proper car! I thought it would be a box!’), but considerable scepticism once the costs and weaknesses were revealed: the potential customers either drove a lot and wouldn’t dream of going electric, or they did short eco-journeys, and already cycled or electric biked locally, keeping a car for the sort of long trips the Leaf couldn’t begin to shake a stick at. Most people were pleasantly surprised that it could be recharged through a normaldomestic plug, but profoundly disappointed that a quick plug-in at home wouldn’t have it hurtling down the motorway at 70mph. All quoted long trips (Coventry, Cornwall, London) that would make it impractical to own.

As elsewhere, the stylists have given the underbonnet layout a familiar look to keep nervous purchasers onside. Note the conventional lead-acid battery for powering 12-volt ancillaries

So who does Nissan think will buy them? Early evidence from America suggests that the typical Leaf buyer is a Yuppy: a college graduate, tech-savvy home-owner in their 40s, earning $125,000 a year. It seems a significant number of these eco-cool baby-boomers drive some 25 miles to work, and in the US at least, enough of them figure that a $30,000 Leaf is the way to go.

Both here and in the States, the green movement is getting quite hot under the collar about perceived anti-electric media bias. We’re as pro-electric as anyone, but the figures just don’t seem to add up.We’d much rather see a battery leasing option, more or less halving the car’s purchase cost to £15,000, plus a leasing charge of, say, £2,000 a year on the batteries. This would do wonders for the resale value, and help owners make better sense of running costs. More importantly, with lithium battery technology improving by the month, it would leave the way open to fit a new upgraded pack as and when the technology is available.

Specification

Nissan Leaf £30,990 (less £5,000 UK government grant)

Weight Car 1,220kg Battery 300kg Total 1,520kg (11/2 tons)

Battery Li-ion

Claimed Capacity 24,000 watt/hours

Replacement Cost Unknown

Max Range 66-87 miles

Full Charge <10hrs

Power Consumption 328Wh/mile

Running Costs 86.5p per mile

UK Distributor Nissan UK www.nissan.co.uk tel 0800 0270075 email evuk@nissan-services.eu

![]()