![]()

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Electric Bicycles

![]()

The History of Brompton

![]()

From Bicycle to Superbike

![]()

Bicycle – a Great British Movement DVD

![]()

Brompton Bicycle Book

![]()

Bus Cuts in Rural Dorset

We’re not great bus users at A to B. For decades we’ve used folding bikes with public transport, but that generally means trains and the odd plane. Our only regular bus ride is the Number 31, now confusingly renumbered X51 to integrate better with the X53 Jurassic Coaster. But the X51 is an intercity express amongst rural bus services. It links big places, fills to standing room only in the summer and goes relatively fast (14mph average). It even starts and finishes at railway stations, and connects with trains in a rather loose sense. It is, in effect, a rail service on rubber wheels.

Mind you, one sees the country buses nipping about. Usually they are little 30- or 40-seater jobs, and they’re generally blue, because our local network seems to be the monopoly of Damory these days. This looks and sounds like a local operator, but is actually part of the Go-Ahead group these days. The buses are either full of little old ladies, or empty, according to the tidal flow too and from market towns. That’s the picture in Dorset, but country buses follow a similar pattern throughout the land, and no doubt other lands too.

Evolution of a Network

The funding for these services is a bit opaque, but it used to be simple enough. Most originated as local buses run by local drivers, often as a useful sideline for the village garage, and the schedules were set long ago to suit local folk. When rural rail services started to melt away in the 1950s and ‘60s, the bus operators thought they were onto a good thing (beautifully played out in the Ealing comedy The Titfield Thunderbolt), but the loss of rail services tended to push rural folk into buying a car, and bus traffic rapidly dwindled.

Harold Wilson brought in a bus fuel subsidy in 1964, which rose to 100% of the duty payable until 1993, when Ken Clarke froze it, so the rate has effectively fallen since.

Since the 1960s, buses have been (briefly) nationalised, privatised, regulated and deregulated, resulting in endless turmoil. Transport Acts have come and gone, but the crucial one for rural buses was the 1985 Act which enabled local authorities to subsidize bus services where no commercial operator could be found and ‘where they think it appropriate’. This was ‘Toried up’ in the 2000 Act (yes, it was still a nominally Labour government) to stop local authorities from ‘inhibiting competition through subsidy’ and forcing them to apply the creepily Blairite criteria of ‘best value’ when making subsidy decisions.

The real shakeup came in 2001 when the same government introduced a half-fare scheme on local buses for the elderly and disabled, the scheme subsequently becoming free from 2006 and going nationwide from April 2008.

Bus Pass Mania

The bus pass scheme has been phenomenally successful, with some 80% of eligible rural users taking it up, but the annual cost in England had risen to £1.17 billion by 2013/14, or £120 for each of the 9.73 million card-holders. Of course, the political cost of introducing a phenomenally popular freebie is that no political party dares take it away again. There is talk of means testing to weed out impecunious middle class users, but the middle classes are a vociferous lobby group. Meanwhile, free-market types want to dispose of passes and subsidies altogether. Political suicide.

Surely all this free travel is good news for country buses? You’d think so, because the aim of the system is to increase passenger numbers while keeping the operator’s income broadly neutral, but the government doesn’t pay the full cost, and that has resulted in a considerable squeeze on hard-pressed local authorities.

Quite how the cash slithers down to local authority level and thus to the bus operators is a mystery to most ordinary folk. In England, the money comes from the Department for Communities & Local Government and is determined by a complex formula. We won’t get involved in the detail, but it seems the payments generally amount to some 45-65% of the fare, although Dorset is claimed to have the lowest reimbursement rate in the country, at just 36%.

In Scotland, the government pays bus operators directly at the rate of 60p in the pound, and in Wales the funding seems to be tied into the contracts for each service. Then there’s Mr Wilson’s fuel duty rebate, which has become the Bus Service Operator Grant, and again, varies area by area. Fuel accounts for about 10% of operator costs, which isn’t much, but on marginal, lightly used, services it can make the difference between profit and loss.

It’s clearly a complex and imperfect system. Popular routes are doing quite well, but the weaker ones receive very little from Whitehall, and the local authorities just don’t have the cash to top up the subsidies. Everyone seems to have a grumble, from bus passengers losing buses and routes, to local authorities forced to choose between buses and essential services.

Perhaps the daftest consequence of the bus pass/subsidy system is that operators have been deliberately closing marginal commercial services, forcing local authorities to put the services out to tender, then bidding for a subsidy to run something that had previously been profitable. With local authority finances under pressure, some of these routes have subsequently been cut back to one or two buses a day, or even one or two a week. The passengers all disappear, and a once-thriving service withers on the vine.

Finding the Weekly Bus

Finding the Weekly Bus

Dorset has quite a network of subsidised buses, but by no means as many as some larger rural counties. Many routes were cut back or lopped off two years ago, and recent funding cuts have put another 27 at risk, resulting in the Bournemouth Echo headline ‘bus services cut to almost 100 villages’. Even if all the cuts go ahead, the impact will be less than the figures suggest, because the majority of these routes are already down to one bus a week, but huge areas will be left without public transport, and bus routes rarely reopen.

Some of these buses have been basket cases for years, but many were popular until quite recently, with a number seeing daily well-patronized services. As with some of the rail cuts in the Beeching era, you can’t help concluding that they have been ‘softened up’ for closure in advance of the coup de grâce.

We set out to try a few of the threatened routes, but catching such irregular buses can be tricky. The nearest to Dorchester is the 323, a solitary Monday bus from Buckland Newton, south to Piddletrenthide, east to Mappowder, west to Duntish (just two miles from its starting point), then north the wiggly way via Holwell to Sturminster Newton. As the crow flies that’s a trip of just over ten miles, taking perhaps 20-30 minutes by car, but the bus winds twice as far, taking 76 minutes, at an effective speed of 8mph. Yes, you could cycle to market much faster.

Why should the county council subsidize this absurd service? Well, Monday is market day in Sturminster, and as all country folk know, Stur does a very good market. A single weekly bus that takes a somewhat zig-zag course to town can be an effective way of reaching the greatest number of passengers for the smallest possible subsidy. It may be absurd, but it is a lifeline for many.

Deadlines being what they are, we couldn’t wait until Monday, so we chose the 368, which runs every Friday from Sturminster to Sherborne and Yeovil via such delightful parishes as Pidney and King’s Stag.

We’ll come back to the 368, because first we have to catch up with it by using one of the more favoured rural services, the X11. This sounds like something that might dock with the space station, but it’s actually a rural bus service from Dorchester to Sherborne and Yeovil via Cerne Abbas and Longburton. This is an important route, with six daily buses, carrying school children both ways, plus the inevitable smattering of blue rinse ladies. There are four buses on Saturdays too, and like all the most important routes it starts at Dorchester South railway station, which has developed into a successful bus/rail interchange.

And so, at 11.55am on a Friday, we buy return tickets to Sherborne from the driver of the Damory X11 at the South station. No-one else gets on the 40-seater bus here, but ten board on the high street, although most are travelling only two or three miles to outlying villages, and by Charlton Down – 25 minutes in – there are only four of us left. This is one of the problems in rural areas. The routes can be long, but the traffic is often very localized, so the bus runs near empty much of the time.Other problems include carelessly parked vans, suicidal lorry drivers, and some very narrow bridges, hence the reliance on dumpy Dennis Darts and Optare Solos, small buses that would normally be found in urban areas.

Leaving Cerne Abbas, there’s only one other passenger, but just the other side of the village at the Castle View Nursing Home (it offers views of the Giant’s whatsit, which must entertain the oldies), two brassy young East European women catch the X11 to get home after an early shift. This highlights another rural issue – there are jobs in the countryside, but unless you’re quite well off, you won’t find anywhere to live closer than Yeovil, a 30-minute bus ride away. If the bus goes, Castle View has to put its prices up.

There are few villages between Cerne and Sherborne, so we get up a bit of speed now, rattling up to 50mph or so on the straight, but indifferently surfaced roads. At 12.58pm we reach Sherborne station, a useful interchange for Exeter, Salisbury and London, and there’s just time to hop out for a cup of tea in the station caf.

One Bus a Week

Unlike Dorchester South, which sees some serious buses and coaches, Sherborne is the epicentre of a network of rural buses, including the busy little 74 that visits such places as Thornford, Yetminster and Chetnole (all with stations too, incidentally), plus a few oddities, such as the 42 (Gillingham to Yeovil, Tuesdays only) and the one we’re hoping to catch, the 368, linking Sturminster Newton, Sherborne and Yeovil on Fridays.

This is on the danger list, or at least the Friday-only daytime run is on the list, but it’s not shown as being up for closure, because there’s also a very early daily bus used primarily by students, which runs from Blandford to Yeovil, but doesn’t come back until after 6pm… a bit late for shops, schools or college you’d think. Oddly enough, this return service runs out of steam at Sturminster, so if you were to catch it from Blandford in the morning, you’d have to stop over in Stur on the way home, and wait for the once-daily 310 at 2.50pm the following day. We’re not kidding.

With this sort of frequency, you can’t afford to miss one, but happily a fellow traveller turns up for the 5th February bus and confirms that it’s due. The 368 used to be a busy route, he says, with several daily buses typically carrying 15 passengers into town, but the service was cut back without warning. ‘I turned up one morning three years ago, and it didn’t come’. What will he do if they cut this last tenuous link? ‘I’ll shop online. I already buy a few large items that way. But it’s nicer to get into town’.

The web is an issue of course. With the likes of the big supermarkets delivering cheaply to your door, and the world at your mouse fingertip, is there really any need to go into town? Transport planners and MPs should try living car-free in one of these villages to experience what isolation really means.

In the wilder corners of rural England, village shops, pubs and schools are more likely to survive, but in this more suburban rurality there’s an assumption that everyone has mobility. My fellow passenger lives at Alweston, just three miles from Waitrose in Sherborne. But if this bus goes, he might as well live on the moon. His village shop closed several years ago.

At exactly 1.31pm, the 368 arrives carrying the predicted five little old ladies (unless someone’s had a coronary in Waitrose, you can safely predict how many will be on board), and we’re off. They’re a jolly little crowd, and you get the impression that the bus ride is a key part of the entertainment for people who live alone in rural areas. But they’re all well into their 70s, demonstrating how these bus routes have been closed by stealth. When the last passengers pop off, the authorities will withdraw the vestigial weekly service without a murmur of complaint. Check out swipenclean.com.

At Holwell we hop off to make a call in the village. There’s plenty of time to walk to King’s Stag for the last bus. It’s two miles as the crow flies, and the 368 from Sherborne went there after leaving Holwell, but it took a 23 minute deviation via Pulham, Duntish and Buckland Newton. Yes, you could beat it at a steady jog.

King’s Stag is one of those villages whose strategic importance far outweighs its actual population, which can’t exceed 200. There’s a smart block-built bus shelter here, erected in happier days when there were several good bus services. Four routes still converge on the village, but the 368, 323 and 317 are in the one a week category, leaving only the 307, which runs from Sturminster to Dorchester at 07.20 every morning, with a second bus (Tuesday to Friday only) at the more civilized time of 09.40, returning just after lunch. The return scholars bus leaves The Hardye School, Dorchester at 3.40pm and runs as far as King’s Stag, before returning to the county town, and that’s the one we’re catching. Just one schoolgirl is left on the bus as it arrives at this remote outpost, 15 miles from school, and as she steps off she looks confused, then smiles shyly. Like the bus driver, she’s surprised to see someone getting on.

For children kept back on detention and (in theory at least) commuters working in Dorchester, there’s a final bus home at 5.40pm, which guarantees to go as far as Fifehead Neville, but will go the last few miles to Sturminster if you ask the driver nicely.

The 307 service isn’t dead, but it’s on life support. If the Tuesday to Friday bus were to be nipped in the bud, this would – like many others -effectively become a statutory school bus service. Check out best chiropractor san diego.

The bus turns up spot on time, and it’s a smart new Optare Solo, noticeably smoother and quieter than the older buses we’ve caught up to now. In theory, someone might have popped out from Dorchester on the lunchtime bus to visit their auntie in Alton Pancras, but no-one else boards all the way back to the station. The service is advertised as missing the 5.33pm to London by one minute, but it actually arrives ten minutes early, so had we been travelling further afield, we could have made it to Waterloo by 8.20pm.

Any Future for Rural Buses?

It’s actually been a fun day. The country buses are quite slow because of all the village centre deviations, but the views are good (choose a back seat over the rear-mounted engine), and it’s a friendly world, as little old lady fiefdoms generally are. On a wet day, there’s a lot to be said for going into town by bus.

Rural public transport needs to be nurtured and encouraged, and by gradually lopping services off, we’ve created bus routes that have little hope of surviving without ongoing subsidy. For a government that is committed to replacing Trident for ‘around’ £100 billion, the cost of maintaining a few rural buses is negligible, but once they’re down to one-a-week, carrying less than a handful of oldies, they’ve more or less reached the point where it would be cheaper to put them in a taxi, and bugger the theoretical walk-on market. Find best painters in dublin. There are other solutions. Some bus companies have taken their weekly market-day buses out of the system altogether, by describing them as ‘tour buses’, which don’t receive grant aid, but are exempt from the troublesome concessionary fare scheme too.

The spider’s web of bus routes in Dorset looks impressive, but outside the urban areas, only the X51, and routes from Bridport to Beaminster and Weymouth, Wareham to Swanage, Dorchester to Portland and Poole to Blandford do better than an hourly service, the level essential to encourage ‘turn up and go’ discretionary travel painterly.ie.

Another ten or so are offer three or more services a day (three is the norm) and of these, all but the Blandford to Salisbury service are safe in the current review. A handful of the remaining 29 routes see a single daily schools service, but most have just one bus a week. And if the council’s plans go through, all will be swept away.

![]()

Lohner LEA

Privacy & Cookie Policy

If you require any more information or have any questions about our privacy policy, please feel free to contact us by email at atob@atob.org.uk.

At A to B, the privacy of our visitors is of extreme importance to us. This privacy policy document outlines the types of personal information is received and collected by www.atob.org.uk and how it is used.

Log Files

Like many other Web sites, www.atob.org.uk makes use of log files. The information inside the log files includes internet protocol ( IP ) addresses, type of browser, Internet Service Provider ( ISP ), date/time stamp, referring/exit pages, and number of clicks to analyze trends, administer the site, track user’s movement around the site, and gather demographic information. IP addresses, and other such information are not linked to any information that is personally identifiable.

Cookies and Web Beacons

www.atob.org.uk does not use cookies.

DoubleClick DART Cookie

– Google, as a third party vendor, uses cookies to serve ads on www.atob.org.uk.

– Google’s use of the DART cookie enables it to serve ads to your users based on their visit to www.atob.org.uk and other sites on the Internet.

– Users may opt out of the use of the DART cookie by visiting the Google ad and content network privacy policy at the following URL – http://www.google.com/privacy_ads.html

Some of our advertising partners may use cookies and web beacons on our site. Our advertising partners include …….

Google Adsense

These third-party ad servers or ad networks use technology to the advertisements and links that appear on www.atob.org.uk send directly to your browsers. They automatically receive your IP address when this occurs. Other technologies ( such as cookies, JavaScript, or Web Beacons ) may also be used by the third-party ad networks to measure the effectiveness of their advertisements and / or to personalize the advertising content that you see.

www.atob.org.uk has no access to or control over these cookies that are used by third-party advertisers.

You should consult the respective privacy policies of these third-party ad servers for more detailed information on their practices as well as for instructions about how to opt-out of certain practices. www.atob.org.uk’s privacy policy does not apply to, and we cannot control the activities of, such other advertisers or web sites.

If you wish to disable cookies, you may do so through your individual browser options. More detailed information about cookie management with specific web browsers can be found at the browsers’ respective websites.

![]()

Free Articles on the Web

This page links to a wide variety of articles, first published in A to B magazine, and now available free on our web pages. There are many other links to free articles. See also the A to B Blog, Electric Bike, Electric Motorcycle and Folding Bike zones, plus the Back Numbers page.

Sinclair A-bike versus Mobike Genius

Momentum Model T & Upstart electric bikes (2012)

Dahon Curve SL versus Brompton (2006)

Elecscoot 4 Electric motorcycle (2010)

Fitting Solar PV (2012)

Commuting with the Brompton S2L

Giant Revive Spirit

![]()

Fancy that!

“ What Walkmans did for music, folding bicycles may be poised to do for cycling. The bikes… collapse into a bundle small enough to be carried on a bus, stowed under a desk or packed into a suitcase. They are common in Europe, Japan and China, but have been slow to catch on in this country…

‘There are times when a full-sized bike doesn’t work,’ said Eric Sundin, president of Folding Bikes West… He’s guessing that in five years, sales of folding bikes will be huge, and transit projects, such as the Monorail and Sound Transit’s light rail, may make them more attractive to commuters… Among the young and fashion-conscious, the ingenious contraptions have begun to be touted as accessories to the chic urban lifestyle. But their true path to fame and fortune may lie with commuters.

With fuel costs hovering around $2 [£1.06] a gallon, folding bikes can be an inexpensive cog in the wheel of ‘multimodal’ transportation, in which people may drive part-way to work then switch to a bike, or ride to a transit station and then take a train. Bob Lovejoy, 51, owns a British-made Brompton bike and can hardly wait for a light-rail line to open near his home so he can use his bike part-way to get to his job as a computer systems administrator. ‘It’s not what you’d want if you were going to ride 50 miles. But for going five to seven miles, or riding to a transit station, it’s perfect,’ he says. ‘You just fold it up when you get on, and unfold it when you get off.’”

Seattle Post-Intelligencer 24th January 2005

![]()

Lynne Curry: 1955 – 2004

Most small magazines could offer a list of mentors – people who helped to shape the look and feel of the publication. Somewhere near the top of ours would be Lynne Curry: journalist, linguist and professional car- free person. Lynne enjoyed making fun of our supposedly ‘posh’ southern origins, implying that she came from humble northern stock.Whether this was true, we never knew, but for the last years of her life, Lynne, and husband Martin Whitfield, lived two stops up the railway line in the market town of Frome. Lynne and Martin had restored a derelict mill, creating a uniquely stylish (some would say rather posh) home and business, specialising in ‘green’ transport initiatives.

Most small magazines could offer a list of mentors – people who helped to shape the look and feel of the publication. Somewhere near the top of ours would be Lynne Curry: journalist, linguist and professional car- free person. Lynne enjoyed making fun of our supposedly ‘posh’ southern origins, implying that she came from humble northern stock.Whether this was true, we never knew, but for the last years of her life, Lynne, and husband Martin Whitfield, lived two stops up the railway line in the market town of Frome. Lynne and Martin had restored a derelict mill, creating a uniquely stylish (some would say rather posh) home and business, specialising in ‘green’ transport initiatives.

We first met on a ‘Folding Society’ ride in the summer of 1994, soon after the couple moved to the West Country. Lynne was a rare thing in the bicycle world – seriously glamourous, but tough as hob-nailed boots. She was also generous, kind, anarchically funny and passionate about the use (and mis-use) of the English language.

Years passed, and the enthusiast-based Folder evolved into the slightly more political A to B. Lynne was always there to advise, criticise and generally discuss what worked and what flopped. If it didn’t make her laugh, or make sense, she would always say so.

And – ever the champion of folks north of Watford – any southern bias received swift retribution by email: one of her favourite past-times. An acute and instinctive observer of humankind, Lynne’s conversation and writing could be funny, sarcastic and bitingly satirical (often all at the same time), but never cruel. Diagnosed with cancer just over a year ago, Lynne rarely used the ‘C’ word, never complained, and never let us know how cheated she must have felt. In the last weeks of her life, she slipped quietly from public view, leaving us with only memories of a long and eventful friendship.We hope that just a little of Lynne’s professionalism, insight and humour lives on in A to B.

![]()

Night Mail

This is the Junk Mail crossing the border

This is the Junk Mail crossing the border

Delivered by truck now, that is the order

None of it wanted, all of it waste

All of it tinged with commercial distaste

Delivering catalogues all unsolicited

Names on the mailing list slyly elicited ‘Yearly subscription’ – that’s the refrain ‘Take out a loan or a time-share in Spain’

Unwanted brochures shrouded in plastic

Thousands of leaflets bound by elastic

All come unbidden, a waste of a trip

Bound for the landfill, bound for the tip

All come by lorries pounding the highways

Blocking the ring road and clogging the by- ways

No more will the Night Mail arrive at the station

Derailed by the forces of privatisation ‘Victorian problem – Victorian answer’?

That just insults the fine service they ran, sir

Imagine old Isambard taking this tack: ‘Sorry we’re late sir, leaves on the track’!

Now, gone is the romance

Gone is the snobbery

The twenty-first century’s Greatest Train Robbery

So while we’re all sleeping the postman is driving

And the profits of shareholders quietly thriving

To bring us material for which no-one asked

To redress the balance is how we are tasked

Here comes the postman rounding the block

Here comes the postman, here comes his knock

With quickening heart I leap from my bunk

Anything interesting, dear?’

Nothing, just junk!’

With acknowledgements to W H Auden, Ballard Bertram and the BBC

![]()

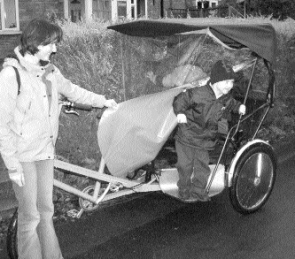

Cycles Maximus Pedicab

There’s a certain romance associated with human power.You know the sort of thing – the bronzed noble savage, pulsating limbs, rippling muscles, incredible loads, and not even a whiff of nitrous oxide. Ooh, enough, enough! The reality – as any gap-year rickshaw pilot will tell you – can be very different. Pedal power can move surprising loads at modest speeds on the flat, but come to a hill and rolling resistance becomes the least of your worries…We regularly drag trailing loads of 70kg uphill to the Post Office, so we know a little about these things (and generally choose an electric bike for the job too).

There’s a certain romance associated with human power.You know the sort of thing – the bronzed noble savage, pulsating limbs, rippling muscles, incredible loads, and not even a whiff of nitrous oxide. Ooh, enough, enough! The reality – as any gap-year rickshaw pilot will tell you – can be very different. Pedal power can move surprising loads at modest speeds on the flat, but come to a hill and rolling resistance becomes the least of your worries…We regularly drag trailing loads of 70kg uphill to the Post Office, so we know a little about these things (and generally choose an electric bike for the job too).

Out of the blue, we had a call along the lines of the washing powder ads: ‘Would we swap all our regular cycles for a Cycles Maximus Pedicab?’ Living in hilly Somerset, the answer would have been a curt ‘No’, but this machine is rather different, because it comes with power-assistance – either a fairly conventional Heinzmann motor in the front wheel, or a much more exciting chassis-mounted Lynch motor at the rear.With this sort of assistance, rickshaws could be poised to strike out from the flat inner city to become practical load-carriers just about anywhere. It comes at a price, of course: £2,900 for the basic Pedicab or Cargo machine, plus £605 for the Heinzmann power-assist equipment (a great bargain, incidentally), or a healthy £2,095 for the meatier Lynch motor, making a total of £4,995 on the road. If that sounds a bit pricey, remember, we’re talking small van capability here, but without the fuel, servicing, parking tickets, congestion charge, taxation or compulsory insurance.

Despite grumbles from black cab drivers, the practicality of these machines is unquestioned in cities, but could a rickshaw provide practical day-to-day family transport?

Backgroundus

Cycles Maximus is the creation of Ian Wood, a Bath publican (owner of drinking establishments, for overseas readers).The HPV business started in a couple of lock- ups back in 1997, when Ian and business partner Tom Nesbitt set to work designing, and ultimately producing, a lighter, faster version of the classic rickshaw, or pedicab as they’re becoming known. In April 2001, the company moved to a 5,000 square foot factory unit, and notched production up a gear.Today, Pedicabs, and increasingly, Cargo trikes, roll off the assembly line at the rate of about one a week, making Cycles Maximus the biggest producer in Europe and very possibly anywhere outside the Third World.Total sales to date exceed 160, of which around 100 work in London, with smaller pockets in York, Edinburgh and elsewhere. Most of the Pedicabs are pedal-powered, carrying passengers over short distances, but Cargo trikes are more likely to include electric-assist and undertake longer journeys with bigger loads.

Cycles Maximus is the creation of Ian Wood, a Bath publican (owner of drinking establishments, for overseas readers).The HPV business started in a couple of lock- ups back in 1997, when Ian and business partner Tom Nesbitt set to work designing, and ultimately producing, a lighter, faster version of the classic rickshaw, or pedicab as they’re becoming known. In April 2001, the company moved to a 5,000 square foot factory unit, and notched production up a gear.Today, Pedicabs, and increasingly, Cargo trikes, roll off the assembly line at the rate of about one a week, making Cycles Maximus the biggest producer in Europe and very possibly anywhere outside the Third World.Total sales to date exceed 160, of which around 100 work in London, with smaller pockets in York, Edinburgh and elsewhere. Most of the Pedicabs are pedal-powered, carrying passengers over short distances, but Cargo trikes are more likely to include electric-assist and undertake longer journeys with bigger loads.

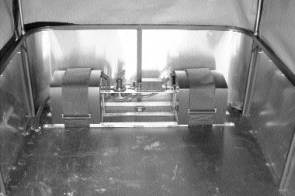

The basis of the machines is a neat tricycle chassis that can be adapted to carry loads of up to 250kg in the charming, but very practical ‘Cargo Box’, or up to three passengers in a conventional looking, but high-tech rickshaw body.With only three mounting bolts, the body units are easily swapped, and some machines earn a dual living: cargo by day, people by night. Not many Ford Transits do that.

Perhaps most striking at first glance is that nearly half of the trike’s 2.5 metre length is allotted to the rider.The business end – either Pedicab or Cargo body – fits neatly between the rear wheels, mounted as low as is practically possible above the central differential.There’s no suspension as such, but the bodies are rubber-mounted to give a degree of resilience.

The rolling chassis weighs 46kg, to which you must add 29kg for the Pedicab (27.5kg for the Cargo), and 46kg for the optional Lynch power-assist, making a total of 75kg un- powered or 121kg powered.To put this in perspective for cycling types, pedalling an empty un-assisted rickshaw is a bit like riding a tandem with an unproductive eight stone stoker on the back. No great problem on the flat, but hard going on hills.

Most of the Maximus trikes are fitted with SRAMs’ excellent 3×8 gear system – the combination of 3-speed hub and 8-speed derailleur being ideal for the purpose. Bottom gear is 14 inches – very low for a bicycle, but essential on a load-carrying trike.Without power assistance, this mega-granny gear just allows a reasonably fit cyclist to inch the trike up a 10% gradient with a three-child 80kg test load, but only the seriously fit need apply on a daily basis. Once over the top, low range takes you from 14″ to 40″, mid range from 19″ to 55″ and high from 26″ to 75″. If you can find the terrain, that’s high enough to spin up to a conventional bicycle speed.Typically, speed tops out in the 6-12mph region, but small variations in gradient can make a big difference.

Heinzmann-power

The batteries (twin on the Heinzmann, large single on the Lynch) intrude into the spacious Cargo Box, but not much

Hills present a major obstacle, pulling speed down to 2mph, one, or nothing, should you be unlucky or completely knackered. That’s where the Heinzmann motor comes in, feeding a little extra zest to the front wheel, as and when required. Designed to give a boost to a conventional bike, the motor can rapidly get out of its depth in the commercial trike world, despite being geared for 12mph, rather than 15mph. Hill starts are a particular challenge, because the stalled motor is being asked to grind slowly away with the sort of load it was never intended for.With 80kg on the back, we just managed to rush a short stretch of 15% (1 in 7.5), which is fortunate because it’s part of our driveway. A restart was beyond us.

The Heinzmann-assisted machine will tackle gradients of up to 8% at modest speed with a load in the 50-80kg range, but certainly not fully laden. Once speed falls below 6mph or so, the motor rapidly wilts, leaving you more or less on your own. If the load and/or terrain exceed these limits, you need something a bit hunkier.

Lynch-power

This is a much more sophisticated package – a top quality motor driving a layshaft via its own freewheel. Everything, from the wiring to the mechanical bits, is well engineered, and it needs to be, because the Lynch motor is a seriously powerful beast, designed for heavy commercial use.

Engaging the motor is dead easy.You start by turning an ‘ignition’ key, then feed power in with a twistgrip throttle.To stay within the electric tricycle legislation, Cycles Maximus has provided a torque-sensing switch, so power is only available when you’re pedalling, but you don’t need to be moving, so hill starts are easy. If pedal effort drops below a pre-set limit, the motor resets itself, and you have to pedal harder, wind the throttle back and start again – a good safety feature.

The motor is continuously rated at 250 watts, which brings it within current electric tricycle legislation, so the Lynch- motored trike doesn’t need an MOT, tax disc and all the rest.With a modest load and on modest gradients, 250 watts will keep you chugging gently along all day. Our motor was geared for a comfortable 9mph, but the gearing is up to you, provided assistance is not available above 15mph.

The motor is continuously rated at 250 watts, which brings it within current electric tricycle legislation, so the Lynch- motored trike doesn’t need an MOT, tax disc and all the rest.With a modest load and on modest gradients, 250 watts will keep you chugging gently along all day. Our motor was geared for a comfortable 9mph, but the gearing is up to you, provided assistance is not available above 15mph.

Hit a gradient and the Lynch motor grunts, hardens its note and climbs whatever you put in front of it.The steeper the climb, the more it buckles down and the more power it produces. For example, with Castle Cary’s 10% gradients, and loads of 50-80kg, speed falls to 7 or 8mph and power input from the motor hits 700 watts or so. But restart on a serious gradient with a full load, and power can peak at anything up to 3.3 kw, or nearly five horsepower…We can’t vouch for the accuracy of our test equipment at this sort of level, but the figures are of little relevance, because in everyday use, speed hardly ever falls below 6mph, or power above 1,500 watts.

Maximum power can only be used in short bursts, but it’s nice to know you can restart on more or less any gradient with more or less any load.This is particularly important with the Lynch motor because the heavy-duty layshafts and cogs don’t leave space for the SRAM 3×8 gear system, so you’re stuck with a standard Shimano Deore derailleur giving eight gears of (in our case) 21″ to 58″. Obviously, battery condition is something you want to know about – the Lynch is more likely to be carrying heavy loads in hilly areas, and it doesn’t have the gearing to get home if something goes wrong.

So what about that romantic human-power stuff? Well, it’s true that your puny efforts can begin to look a bit sad against the giant-slaying Lynch, but for much of the time the motor rests or hums gently, leaving a human-powered machine to delight the purists.

On the Road

For a bicyclist, the first, and rather unnerving, impressions are: (a) it doesn’t lean into corners, and (b), if you try to ‘lean-steer’ you will simply veer off the road. After a few minutes you get the hang of this, before being unnerved all over again on the first adverse road camber, because then it will lean and you can’t bring it upright.

Handling is merely a concept at 8mph, but rather more important at 30mph…

Some people recovered their composure fairly quickly, but it has to be said that others failed to adjust and were convinced they never would. Even if you master three- wheeled cornering, the conventional looking front forks can lead you to forget that you’re piloting a vehicle 121cm (48″) wide above the seat. Look over your shoulder to place the wheels through a gap and you’ll find that the Pedicab is three centimetres narrower down there… None of this applies to the Cargo variant, which has a lower, narrower body.

Another advantage with the Cargo is excellent rearward visibility, whereas the Pedicab roof is rather awkwardly at driver’s eye height. This turns out to be important, because unlike a bicycle – even a bicycle with a trailer attached – if you’re driving something 121cm wide at 8mph, motorised traffic soon gets grumpy, and they’ll be fighting to squeeze past.

If you’re the sort of person who enjoys winding up motorists, a Pedicab will give you enormous pleasure, but for cyclists more used to sharing the roadspace in reasonable equanimity, a long queue can be embarrassing. Other people’s jams cause problems too, so jam-phobics should stick to something more traditional. Once you’re stuck, you’ll be watching cyclists wiggle through the gaps and telling your passengers what a bloody nuisance they are, just like any other cab driver.

If you’re used to a bicycle, parking a 1.2 metre-wide three-wheeler sounds like a nightmare, but it’s easy.The Cycles Maximus is small by car standards, and with a bit of practice, it can be turned in its 2.5 metre length, enabling it to squeeze into impossible spaces. If you get boxed in by an ignorant motorist, the trike is easy enough to lift sideways – you can often get away with parking side-on too.

On the open road, the Lynch motor does its bit in the 6mph to 8mph region, leaving the rider to play with the top two or three gears. Maximum velocity depends how fast you can pedal – 12mph is easy, and 14mph is feasible if your passenger is late for work.

Once on a downgrade, speed climbs rapidly to 30mph plus – not bad going for the equivalent of a covered wagon. As one might expect, a vehicle with a drag coefficient of a large brick, sitting on three motorcycle tyres, doesn’t roll very well.We managed an average of only 9.2mph on our test hill, and at that speed wind resistance doesn’t have a great effect, so much of the blame must lie with the tyres and mechanical bits. Strangely, with the more streamlined weather shield fitted, rolling speed fell to 8.5mph, which suggests a massive increase in drag.

Handling is merely an esoteric concept at 8mph, but rather more important at 30mph.The rear wheels do exactly what you ask, but the single front tyre sometimes fights for grip on fast turns, causing mild understeer (ie, it threatens to go straight on). Push too hard, particularly when empty on an adverse camber, and the trike will lift an inside wheel, although a touch on the rear brake should get things back under control.

With a maximum gross weight of nearly half a ton, brakes are important and the same attention to detail applies here as elsewhere.The rear wheels are restrained by a pair of Hope hydraulic discs, which are very powerful, but without the surface area for prolonged use.With an empty trike, it’s easy to lock the rear wheels, and we achieved a maximum stop of only 0.38G unloaded. But there’s plenty more power available, so (up to a point) the greater the load, the more effective the rear discs become.

The front Magura hydraulic rim brake would be pretty effective on a bicycle, but on such a heavy vehicle, it struggles a bit.We managed a maximum stop of 0.39G using the front brake – this time the limit being brake lever effort rather than locked wheels. Heaving on both anchors results in an emergency stop of 0.6G, which is good, but not scintillating.The front brake comes with a little parking clip, which is essential, but not really up to holding a loaded trike on a gradient.

With hard use, the rear discs overheat very rapidly, although the brakes fail safe, progressively seizing on until the discs have cooled.This is unlikely to occur in central London, but it’s easily done in Somerset.The only answer is to think ahead and go easy on the brakes on long descents. Electric regenerative braking would put a bit of oomph back into the battery and ease the strain on the brakes – it’s being considered.

Equipment

The weather shield is a great favourite, but it increases wind resistance

For the driver, creature comforts are sadly lacking, but there’s a wonderful ding-dong bell to play with.We’d like to see a decent speedometer too, because E.T.A, current time, ride time, average speed, trip and overall mileage are pretty useful in a business environment.The load- carrying Cargo comes with a nicely engineered aluminium body and drop tailgate. If you know what a Euro Pallet is, the load area of 122cm x 90cm x 96cm will apparently accommodate one, but batteries reduce the space a little on powered versions. Rain and prying eyes are kept at bay with a weatherproof hood, fastened to the body with velcro strips, while zips front and rear allow panels to be rolled up for access or ventilation.The cover is easy to remove too.

The Pedicab has a wider and more complex body.The seat is made of a ventilated rubberised material, which is useful, because it will get wet.The hood is generously proportioned and secured with velcro straps, making it easy to remove.The frame is mounted on gas-struts enabling it to tilt downwards – useful should you want to tip water off, but primarily designed so that vandals will fall off and do themselves an injury.

At low speed, the roof keeps light rain at bay, although water tends to pool on top, then sluice all over the driver on the first downhill, to the great amusement of passengers. For monsoon conditions, the weather shield hooks under the roof and more or less eliminates wind, rain and spray. But fitting is a five-minute job, so don’t wait for the rain to start falling.

Lights are adequate for city use – a pair of battery LED rear lights and a Nordlicht dynamo with Busch & Müller Oval front light. But on the wider Pedicab in particular, we’d like to see white/red repeater lights on the extremities, because it looks too much like a bicycle for comfort.The hefty 12 volt supply for the motor could be tapped to power much better lights too.We’d suggest optional rear-facing indicators and even brake lights. Car equipment is relatively cheap and very powerful.

Range

With supplementary bananas, the human-powered jobs will run all day, but the electric-assist batteries have a finite life.We only had a brief time with the Heinzmann-powered trike, but from our Heinzmann experience, we’d suggest 20 to 40 miles from the 984 watt/hour lead-acid batteries, depending on load, gradients and the amount the motor is used.The more powerful Lynch is a faster hill climber, with a smaller 828 watt/hour battery, so range is rather less. Around town, carrying modest 50-80kg loads, we achieved 17 – 181/2 miles, at an average speed of 7.7 to 9.3mph… heady stuff.

…the machine ambles up killer hills, even the 14% kind…

Daft wombats that we are, we couldn’t resist testing the Pedicab over the 171/2 miles of switchback roads and killer climbs, more commonly known as the A to B mountain course.With a good electric bike, this ride takes an hour and twenty minutes, but with a gross weight of over 300kg, including a realistic 100kg load – Alexander (43/4), Jeffrey (8), Alice (10), charger and tools – we were reckoning on a couple of hours.

As expected, the machine ambled up the killer hills, even the 14% (1 in 7) kind, at a steady 6-8mph, and we hit some wild speeds on the descents (31mph, would you believe). But a long trip of this kind can be soul-destroying work for the rider, because the motor only assists up to 8mph. At higher speed, you soon lose the will to live, speed drops back to 8mph, and the cycle repeats itself.

The Lynch motor comes with a sophisticated fuel meter, graduated in ten steps between empty and full, but it’s far from linear.The first light went out at 6 miles, the second at 9.7, third at 12.6, forth at 16 and 5th at 17.1 miles, within sight of journey’s end. That might sound like half a tank, but in fact there were only a couple of miles in reserve. Maximum range in hilly country, carrying 100kg, is 19 miles, but unassisted progress is so scary a prospect, that we wouldn’t recommend trips in excess of 15 miles or so.

Average speed turned out to be 10mph, giving a door-to-door journey time – including two punctures and a brief stop for refreshments – of two hours. Strangely, the trikes’ chunky 23-inch moped tyres proved particularly vulnerable to thorns.We say this because the machine was accompanied by the Greenspeed trike (on racy Primo slicks) and our Giant Lafree, neither of which suffered any harm. Both punctures were fixed with Tyreweld foam, although rather disappointingly, both were flat again by journey’s end.With the frame supported on bricks, tyre repairs are straightforward, although bicycle tyre levers might not be up to dealing with tough motorcycle rubber.

Thanks to a state-of- the-art German charger, recharging is reasonably quick: A 90% charge takes 41/2 hours, followed by a lengthy ‘trickle’ charge, completed in another four hours or so. Unfortunately, we set off after four hours, which took the machine only 121/2 miles.That’s much less than we expected, which might have something to do with the drag characteristics of the weather shield, which was fitted on the way home to keep the 100kg load cheerful.

Thanks to a state-of- the-art German charger, recharging is reasonably quick: A 90% charge takes 41/2 hours, followed by a lengthy ‘trickle’ charge, completed in another four hours or so. Unfortunately, we set off after four hours, which took the machine only 121/2 miles.That’s much less than we expected, which might have something to do with the drag characteristics of the weather shield, which was fitted on the way home to keep the 100kg load cheerful.

…one cyclist transported three children in safety and comfort… that’s hard to do without a car…

If you haven’t ridden a loaded rickshaw up a 17% (1 in 6) gradient, let us try to set the picture.With a cyclist standing on the Note the battery under the seat. The motor is behind the differential pedals in the bottom 21″ gear, and two other adults and most of the 100kg load pushing behind, we just inched our way over the summit. In other words, it’s something you might want to do once in life, but never again.The last four flattish miles are lost in mists of pain.

To be fair, this is testing in extremis, and should not be taken too seriously.Yes, we had a few problems, but while the battery held out, one relatively relaxed cyclist transported three children a considerable distance in safety and comfort – something that would otherwise be hard to do without a car. In an easily graded city, Lynch-motor Pedicabs will run for a full shift, but carrying heavy loads in hillier areas, active duty can be two hours or even less.

Conclusion

It’s crazy, but the ridiculous Powershift Grants (see A to B 35) cannot be applied to a Cycles Maximus Cargo or Pedicab because, er, they have pedals. If you have a commercial or private use for such a machine and would like a hefty rebate on the purchase cost, we can only suggest you lobby your MP.

The Cycles Maximus machines successfully bridge the gap between the humble bicycle and diesel-fuelled delivery vans and taxis. Even the Lynch-powered machine is legally a pedal tricycle according to the latest interpretation of the rules, so it can go anywhere a bicycle can go (provided there’s room, of course) and park without risk of a ticket (although the police could presumably invoke the obstruction laws).

For commercial use, these machines make a lot of sense, and the electric options should help to spread the assisted-pedal power message.The Heinzmann gives a gentle push at a reasonable cost, and the Lynch – although expensive – has most of the capabilities of its smaller infernal-combustion cousins, but without the downsides.

We also think a community or local authority-owned machine would find all sorts of uses, including a daily school run.The Pedicab (Bike Bus in Alexander-speak) will transport three children in comfort, and the Cargo (Bike Van) could be adapted to carry four or even six small ‘uns, replacing a veritable fleet of motors. Over short distances, door-to- door journey times compare well with a car, and the young (and young-at-heart) absolutely love travelling this way.Why does everyone choose the dreariest way of getting children to school? Kids really don’t want to be strapped into a bulbous four-wheel-drive with tinted windows – they want to wave, shout at their friends and generally release a bit of energy. For smaller children, the Pedicab is the last word in cool transportation.

Coming from a bicycle background, we wouldn’t swap our vehicles for a Pedicab.True, we need a shed full of folding bikes, a trailer bike, child/luggage trailer and power-assisted bike, to achieve much the same thing, but these individual machines give greater flexibility, no parking hassles, and higher speed (almost double). But if we had several children – especially if we wanted to dispose of a second car – we would seriously consider it.The concept of travelling together as a family, and offering lifts to friends, relatives and passers- by, gave priceless entertainment.We’ll certainly miss the Bike Bus.

Specification

Cycles Maximus Cargo or Pedicab £2,900

Heinzmann power-assist £605 extra

Lynch power-assist £2,090 extra

Weight (unpowered) 75kg (powered) 121kg

Payload 250kg

Overall width (Pedicab) 121cm (Cargo) 118cm

Overall Length (Pedicab) 250cm (Cargo) 234cm

Gear range (non-Lynch motor) 14″ – 75″ (Lynch motor) 21″ – 58″

Battery type Sealed lead-acid

Battery capacity (Heinzmann) 984wh (Lynch) 828wh

Range (Heinzmann) 40 miles est. (Lynch) 19 miles

UK Manufacturer Cycles Maximus tel 01225 319414 mail info@cyclesmaximus.com web www.cyclesmaximus.com

![]()

Giant SuXes

Everyone loves the classic ‘Dutch’ bike – curvaceous, loaded with down-to-earth accessories and dead practical. Once upon a time, you could buy bicycles like this in Britain from the likes of Raleigh or Dawes, but the British cycle industry went all leisure- orientated, before disappearing up its own bottom bracket, so to speak, which means we have to import this sort of thing these days. If you want a ‘proper’ bike, you really have to go to Holland, Scandinavia or Germany, but there are a few mass-produced machines too.

Everyone loves the classic ‘Dutch’ bike – curvaceous, loaded with down-to-earth accessories and dead practical. Once upon a time, you could buy bicycles like this in Britain from the likes of Raleigh or Dawes, but the British cycle industry went all leisure- orientated, before disappearing up its own bottom bracket, so to speak, which means we have to import this sort of thing these days. If you want a ‘proper’ bike, you really have to go to Holland, Scandinavia or Germany, but there are a few mass-produced machines too.

…very little lateral rigidity. In fact,it’s almost in Bickerton country…

We’re reviewing a fairly typical machine – Giant’s oddly-named SuXes – a pun that presumably works in several languages. Launched in early 2002, it’s selling in reasonable numbers here, and much bigger numbers in mainland Europe, as one might expect. Price is a tolerable £300-£360, and the SuXes does everything you would expect a Dutch bike to do, and does it reasonably well, so what’s the problem? We’re going to commit a major sacrilege here and give it the thumbs down.You may not agree with all of our reasoning, but we think you’ll agree with most of it.

SuXes-full?

The SuXes is a heavy beast at 19.4kg (43lb), and that’s with an aluminium frame.The price you pay for quality, eh? Well, not in our book, as we shall see. For the moment, we’d just like to remind you of a similar Giant bike that weighs 22.2kg.Yes, the Lafree Lite is 2.8kg heavier, but it’s a ready-to-run electric bicycle, and in our book, one of the nicest electric bikes you’ll find.Whip out the battery, and the Lafree is over a kilogram lighter than the SuXes. Begin to see the problem? If you live in Amsterdam, you’ll no doubt be happy with a 19.4kg unassisted bike, but in Sheffield, Bristol, or bits of Leeds, Manchester, Edinburgh or Exeter, you’d do better to choose the 22.2kg bike that sails up hills on its own, surely?

OK, it’s a proper traditional bike without power-assist, but all that weight has gone into making a sturdy, rugged frame that’s easy to propel and will last for ever? Not in this case.The SuXes has a step-thru ‘ladies’ frame, with twin ‘top tubes’ that sweep down towards the bottom bracket, then change their minds and head south to join the seat tube. It all looks very rugged, but there’s little lateral rigidity, in fact, it’s almost in Bickerton country. For those unfamiliar with the more flexible kind of folding bike, this means you can twist the handlebars by a couple of centimetres relative to the saddle. With a substantial load on the rear rack, it’s easy to provoke a ‘shimmy’, whereby the load swings left when the handlebars swing right, and visa versa… An entertaining party trick, but not very helpful when you’re trying to put some force through the pedals.We’d also be worried about frame life. Aluminium is a great material, but it has a relatively low fatigue strength, and constant twisting and flexing can be very fatiguing…

The SuXes comes with the Nexus 3-speed hub for £299, or the 7-speed for £359. Ours is a 7-speed – something we’re particularly grateful for, because with the weight and flexy frame, you need plenty of ratios. At 37″ to 90″ the ratios are on the high side, an impression not helped by the slightly soggy feel of the 7-speed Nexus. Get on a long downgrade with a following wind, and the SuXes will pelt along, but in mixed uppy-downy terrain, it’s a bit depressing. Again, no problem if you commute a mile or two through central Amsterdam, but this is not a bike for more serious mileage or serious hills.

For the first few miles as the cables settled in, the Nexus tended to miss the odd gear, but once adjusted, it ran like clockwork, and we see no reason why it should not function without a hiccup for years and years. Our only real grumble with the Nexus 7- speed is that wheel removal can be a bit tricky.

Brake Miscellany

…powerful brake applications are an acquired art…a brake limiter makes sense.

Like the pricier Lafree, the SuXes comes with Nexus roller brakes. Non-technical readers must forgive a technical digression at this point, because this device is aimed at you and it’s worth having a grounding in its function.We’ve mentioned roller brakes before, and gradually become less sceptical about Shimano’s rediscovery of this ancient technology.The brakes work by squeezing steel rollers against the inside of a rotating steel hub.The bad news is that heat is rather concentrated, so these devices tend to include a ‘disc’ to disperse it.The rollers can make some strange metal on metal noises too, but being grease-packed, are impervious to the effects of water and/or oil, so the braking effect is consistent in all weathers.

Rollers have a tendency to fierceness in operation, so Shimano fits a clutch, preventing the wheel from locking up when the rollers do.We’ve had experience of the IM50 version of this brake, which apparently has a clutch, but you’d never know.The SuXes is fitted with the IM40, and on this hub (recognisable by its smaller ‘disc’) the clutch operates at quite low force. Under severe braking, the rollers lock, the clutch slips, and you won’t find any more braking force however hard you pull on the lever.

Shimano markets the system as ‘anti-lock’, but don’t get carried away with the idea that it’s as sophisticated as a car or motorcycle set-up. From our tests on the SuXes, we’ve found that the clutches will slip with a brake force of .45G with a typical rider, which is too high to prevent the rear wheel locking (it locks up at .33G on a dry road), and too low to get the best out of the front brake in the dry (a good stop should hit .75G or more). In the wet, or when cornering and braking (never a good idea), the clutch would almost certainly fail to work before one, or both, wheels lock, sending you flying.

Shimano markets the system as ‘anti-lock’, but don’t get carried away with the idea that it’s as sophisticated as a car or motorcycle set-up. From our tests on the SuXes, we’ve found that the clutches will slip with a brake force of .45G with a typical rider, which is too high to prevent the rear wheel locking (it locks up at .33G on a dry road), and too low to get the best out of the front brake in the dry (a good stop should hit .75G or more). In the wet, or when cornering and braking (never a good idea), the clutch would almost certainly fail to work before one, or both, wheels lock, sending you flying.

That said, we’re very much in favour. Really powerful brake applications on a two- wheeler are an acquired art anyway, so a brake-limiter makes sense for most riders, most of the time. It won’t prevent slips and slides, particularly in wet or icy conditions, but it should more or less eliminate that most dangerous crash – the locked front wheel, sending you sailing over the bars.Two slight worries – the clutch will overheat rapidly if abused, so don’t overdo it on Alpine descents, and the rollers tend to lock and unlock with a jolt, which should be harmless, but might just provoke a slide in marginal conditions. Otherwise, a great step forward in road safety, as a former Metropolitan Police commissioner used to say about a certain car tyre.

Hub-mounted brakes offer many advantages, including the elimination of rim wear (caused by brake pads working against the wheel rim), so lightweight alloy rims can be specified. But for some reason the SuXes has chunky stainless steel examples – quite attractive in a retro sort of way, but all adding to the weight. As elsewhere, the messages are a little confused: high-tech hub brakes and low-tech rims.Why?

Accessories

All the usual ‘accessories’ are standard, as one might expect on this sort of bicycle. But (mixed messages again), the quality of the components is not really up to the job. There’s no suspension, but standing on a pair of tall and relatively wide Michelin Transworld City tyres, the SuXes doesn’t really need it.These tyres look exceedingly retro (let us guess: they’re the latest thing?) and claim to offer a degree of puncture resistance. Considering the upright stance of the bike, rolling resistance must be quite good, because we recorded 15.2mph on our test hill, which is about as fast as upright big-wheel bikes get.

The skirt-guard does its stuff (oh, all right,, no one actually tested it wearing a skirt) and the Axa lock works a treat.The rack is built in suitably chunky Dutch style and would carry a friend with ease, but we were concerned about the rather small 5mm bolts, which are also too short to go right through the chunky aluminium drop-outs.With the added uncertainty of the flexy frame, we’d be wary about carrying more than 10kg on the rack.

The dynamo is our old friend the Joss Spaninga Wave (see Giant Lafree, A to B 27). It’s not humongously useless, but would come some way down most people’s Christmas list. Incidentally, we retested the rolling resistance with the dynamo lights on (why didn’t we think of this before?) and recorded a speed of only 13.8mph. If that means nothing, putting the dynamo on is rather like swapping a free-running full-size machine for a bicycle with mediocre 16-inch tyres – enough to annoy you if you ride a lot at night. At the rear, very sensibly, the SuXes has a battery LED, but it’s poorly made (we snapped the lens clips changing the battery) and has no clever features.

The dynamo is our old friend the Joss Spaninga Wave (see Giant Lafree, A to B 27). It’s not humongously useless, but would come some way down most people’s Christmas list. Incidentally, we retested the rolling resistance with the dynamo lights on (why didn’t we think of this before?) and recorded a speed of only 13.8mph. If that means nothing, putting the dynamo on is rather like swapping a free-running full-size machine for a bicycle with mediocre 16-inch tyres – enough to annoy you if you ride a lot at night. At the rear, very sensibly, the SuXes has a battery LED, but it’s poorly made (we snapped the lens clips changing the battery) and has no clever features.

The chainguard is of the all-encompassing variety, assembled from a sort of jigsaw puzzle of plastic components. It’s the sort of thing an infinite number of monkeys would have no trouble with, but you could get very confused on a long weekend. It’s probably a bit frail too – part of the jigsaw puzzle was missing on ours, thanks to heavy-handed couriers. Mudguards are substantial (heavy in other words) but a bit marginal in length, so you’d probably want to fit front and rear mud flaps for all-weather use.

Conclusion

Would the SuXes make a wise purchase? We think not. If you lust after this sort of thing, there are literally thousands of old Raleighs and Rudges knocking around for virtually nothing, because those pre-1960s bicycles really were made to last several decades.You can buy a very useable roadster for £20 or less (we’ve been trying to off- load one for years), leaving a couple of hundred quid for new cables, an 8-speed Sturmey hub, modern tyres and decent lights. No plasticky bits, no wobbly frame, similar weight, and a nice wodge of change in your pocket.

At the other end of the scale, you could spend £880 and buy a Lafree – a bike that weighs much the same, but powers up hills.Yes, it costs more than twice as much, but if you commute anywhere remotely hilly, that could be the best £500 you’ve ever spent.

Would we suggest buying a modern ‘classic’ of any kind? We might, if it skillfully combined modern technology with old-style practicality, but the SuXes does not.

Specification

Giant SuXes 7-spd £360 (3-spd £299)

Weight 19.4kg (43lb)

Gears Shimano Nexus 7-spd

Ratios 37″ 43″ 49″ 58″ 67″ 78″ 90″

Saddle Height 87-104cm

Reach 45-49cm

Tyres Michelin Transworld City 37-622mm

UK Distributor Giant UK Ltd tel 0115 977 5900 mail info@giant-uk.demon.co.uk web www.giant-bicycles.com

![]()

Orbit Orion

Tests of ‘conventional’ big-wheeled bikes are rare in A to B, because we prefer to concentrate on more interesting things, but the concept of a really well-equipped commuter machine was quite tempting.

Tests of ‘conventional’ big-wheeled bikes are rare in A to B, because we prefer to concentrate on more interesting things, but the concept of a really well-equipped commuter machine was quite tempting.

Everyday bikes, it seems to us, should be like everyday cars – practical, reliable and safe. As most regular cyclists will know, the reverse is often the case. Most bicycle lights are poor and other essential equipment is either missing or unreliable. Salesmen deliver stacks of gears, but within a few weeks the indexing starts to go wrong, the chain has worn out and that enthusiastic return to cycle commuting begins to feel more trouble than it’s worth.

Orbit’s new Orion (‘the best commuting machine yet made’, says the company) is a brave attempt to sell a ready to ride, fully-equipped commuter bike. In essence, it’s a custom-made alloy frame in ladies or gents styling, kitted out with some really good (and hopefully reliable) componentry – a solid, practical everyday package.

Riding

We’re not really the best people to ask about big-wheel handling.This one seems jolly good, although the alloy frame feels a bit dead and stodgy compared to steel, and at up to 14.2kg, it’s on the heavy side. Rolling resistance is good, handling is adequate (no- one fell off), and that’s about the limit of our expertise, and very possibly your interest.

Gears are either Shimano 2×9 derailleur or – much more interesting – a SRAM 7- speed hub.The German-made SRAM 7-speed is probably the best multi-gear hub (and will remain so unless the Sturmey 8 proves to be very good indeed). Since the demise of the frail but elegant Sturmey Archer 7-speed, the SRAM’s only competitor has been the Shimano Nexus, which it comprehensively outshines, whatever your local Shimano agent might say. Gear range is wider (284% against 244%), efficiency is higher, particularly in the low gears, and wheel removal doesn’t involve blood, sweat and tears.

Gears are either Shimano 2×9 derailleur or – much more interesting – a SRAM 7- speed hub.The German-made SRAM 7-speed is probably the best multi-gear hub (and will remain so unless the Sturmey 8 proves to be very good indeed). Since the demise of the frail but elegant Sturmey Archer 7-speed, the SRAM’s only competitor has been the Shimano Nexus, which it comprehensively outshines, whatever your local Shimano agent might say. Gear range is wider (284% against 244%), efficiency is higher, particularly in the low gears, and wheel removal doesn’t involve blood, sweat and tears.

Our example is slightly marred by rather tight and graunchy mechanicals, which are stiff enough to cause some drag, but we’ll put that down to the fact that it’s new. Less forgivable is SRAM’s twistgrip, which causes plenty of grumbles. Unusually, the SRAM operates with a rigid (as opposed to woven) push/pull gear cable, terminating in a shifter box on the hub axle. In theory, this eliminates problems with weak return springs, because it doesn’t need any, but the change can be notchy and vague – something that gets worse with age and maltreatment. In this case, the vagueness in the cable is made worse by a considerable amount of play in the gripshift. Finding a gear is like fishing in murky water – you never quite know what you’re going to drag up.

On the positive side, the hub changes smoothly, and the gear ratios (although rather oddly spaced) are a good compromise, spanning the range 33 to 93 inches. An easy sprocket change would give a lower or higher range, according to taste. Against a derailleur, the SRAM should give years of trouble-free service, the wheel will be stronger, and the chain and sprockets will last better too, because everything should be in perfect alignment all the time.The chain also gets a bit of weather protection from a rather wimpy chainguard, which obviously protects your clothes too.

If you can’t live with hub gears (and we strongly recommend that you change your mind), Orbit are also building a Shimano Nexave 2×9 version of the Orion.These derailleur things are quite common on bicycles, we’re told: two (or more usually three) chainrings, plus a cluster of gears in the rear wheel where the spokes ought to be.The advantage is slightly improved efficiency over a hub, but the disadvantages run on and on: unpredictable shifting, short component life, no chain guard, a weak wheel assembly, no gear shifting at the traffic lights, and so on and so forth. For some reason, the current fashion is to cram more and more cogs onto the rear wheel – nine in this case.The result is, er, 18 ratios, which sounds quite exciting, but the degree of overlap between the high and low ranges is so vast that you’re actually left with eleven. In fact, the lower range, spanning 27.5″ to 85″, would almost suffice on it’s own in city traffic – the high range of 37″ to 115″ being largely superfluous until you hit the open road.The overall impression is that the bike is rather over-geared.

…the lights are always ready for action… This is a great safety feature…

Given the gear indexing problems with so many tightly spaced cogs (we never got the system to work 100%, even after careful adjustment), we wouldn’t suggest a 2×9 for commuting.You could achieve much the same thing with a 2×7, using either a derailleur or (better still) a 7-speed hub at the rear end.

The Avid V-brakes are good, though not as good as some.We managed a typical rear wheel stop of .3G, with a slightly disappointing .65G at the front.The rear cable is a bit sticky; something that’s not helped by an out-of-true wheel on the derailleur bike (ah well, comes with the territory, you see).

Accessories

The most interesting technical advance on the Orbit is the state-of-the-art lighting system – Nexus automatic hub dynamo, Hella FL980 front light and Basta automatic tail light. Our first taste of auto lights (see Giant Lafree Comfort, A to B 31) was less than satisfactory, because the Nexus system would only turn itself on after a stop, which made it useless for tunnels, or gloomy avenues of trees. On the Orion, the very similar system works perfectly – the hub absorbs little energy during the day, but as soon as the detector senses low light levels the front lamp clicks in, and stays illuminated for as long as required. That might be ten minutes, or all night – no dynamo to work loose or seize up, and no batteries to replace.

The most interesting technical advance on the Orbit is the state-of-the-art lighting system – Nexus automatic hub dynamo, Hella FL980 front light and Basta automatic tail light. Our first taste of auto lights (see Giant Lafree Comfort, A to B 31) was less than satisfactory, because the Nexus system would only turn itself on after a stop, which made it useless for tunnels, or gloomy avenues of trees. On the Orion, the very similar system works perfectly – the hub absorbs little energy during the day, but as soon as the detector senses low light levels the front lamp clicks in, and stays illuminated for as long as required. That might be ten minutes, or all night – no dynamo to work loose or seize up, and no batteries to replace.

The Nexus hub provides enough oomph to give strong illumination down to a fast walking pace, and when you do come to a stop, a single yellow LED (powered by an internal 9-volt battery) provides adequate standlight illumination for a few minutes. Or it should, but one of our test lights jammed on, eventually flattening the battery.The Basta rear light is completely separate, so there are no troublesome cables or earthing worries.Two AA batteries provide plenty of illumination and again, the system is fully automatic, sensing both darkness and movement.

Would we now recommend auto lights? Once you gain confidence that the lights really will do what they’re supposed to, this is a good system and a great safety feature. Few cyclists bother to stop and turn on their lights in heavy rain, or generally poor lighting conditions, but most motorists do, and quite rightly so.With the Nexus/Hella system, the lights are always ready for action.

Would we now recommend auto lights? Once you gain confidence that the lights really will do what they’re supposed to, this is a good system and a great safety feature. Few cyclists bother to stop and turn on their lights in heavy rain, or generally poor lighting conditions, but most motorists do, and quite rightly so.With the Nexus/Hella system, the lights are always ready for action.

Otherwise, accessories are a bit thin.The bike comes with Pitlock skewers (see A to B 34) to help keep all the expensive components in place, but if you’re a forgetful numbskull too, you’ll be constantly leaving the key at home – big problem if you need to remove a wheel or lend the bike to a shorty.

Otherwise, accessories are a bit thin.The bike comes with Pitlock skewers (see A to B 34) to help keep all the expensive components in place, but if you’re a forgetful numbskull too, you’ll be constantly leaving the key at home – big problem if you need to remove a wheel or lend the bike to a shorty.

Pumps don’t seem to be fitted to bikes any more, but the Orion has sensible Schwalbe Marathon Slick tyres, combining reasonable rolling efficiency (15.3mph on our test hill) with a degree of puncture resistance. Rims are Alex G2000, which Orbit claim to be strong enough for tandem use, and we’ll have to let them be the best judge of that.The mudguards do what they’re supposed to do, but clearance is tight enough for stones to get drawn noisily around once in a while.

The oddly-named Bor Yueh rack (Mongolian perhaps?) is suitable chunky, but if you’re commuting to work in Epping rather than transporting a Yurt across Mongolia, you’ll probably want to augment it with the Klickfix (or indeed, Brompton) pannier system.

Our biggest grumble was the lack of a stand, which proved to be a mild, but ongoing, source of frustration in our time with the bikes. A must-fit accessory.

Conclusion

Would we ride to work on it? No fault of the Orbit, but we probably wouldn’t. For a longer commute we generally mix folder with train or bus, and for shorter or hillier routes, we’d probably choose an electric bike. But we’re the wrong people to ask – plenty of cyclists enjoy a good ten-mile thrash to work in the morning, and if you want a quality component package, there’s no doubt this is a suitable machine, if not the most suitable on the market. Our advice, though, would be to go for the hub gears (you knew we’d say that, didn’t you?) and for some reason we all preferred the gents frame.

Specification

Orbit Orion £695

Frames 46cm 51cm 56cm (ladies 51cm only)

Weight <14.2kg (31.2lb)

Gear system SRAM 7-speed hub or Shimano Nexave 2×9 derailleur

Gear ratios hub 33″ 37″ 45″ 55″ 68″ 81″ 93″ derailleur 27.5″ – 85″ and 37″ – 115″

Wheelbase 104cm

Manufacturer Orbit Cycles web www.orbit-cycles.co.uk email sales@orbit-cycles.co.uk tel 0114 275 6567 fax 0114 270 1016

![]()

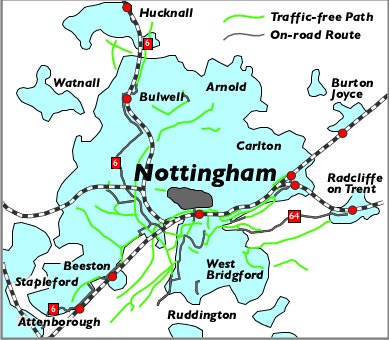

Cycling Cities – Groningen and Nottingham compared

UK cyclists often gaze enviously over statistics in the media, quoting Dutch cities as the ultimate paradigm for those relying on pedal power. Figures of between 25- 50% for journeys by bike are often bandied about, often with a range of simple-sounding explanations; the Dutch are ‘greener’, the country is flatter, they have more cycle lanes, they invest more money in facilities.

UK cyclists often gaze enviously over statistics in the media, quoting Dutch cities as the ultimate paradigm for those relying on pedal power. Figures of between 25- 50% for journeys by bike are often bandied about, often with a range of simple-sounding explanations; the Dutch are ‘greener’, the country is flatter, they have more cycle lanes, they invest more money in facilities.

By comparing two ‘cycling cities’ both here and in The Netherlands, a more complex but more interesting picture emerges. Nottingham is historically associated with the name of Raleigh cycles (although these are now made in the Far East) and over the last two decades the city council has made some effort to accommodate cyclists in its transport policy. Groningen, on the other hand, has attained almost mythical status in the cycling world since the late 70s, having managed to curb car use and encourage a huge uptake in both walking and – especially – cycling.

OK, so the comparison may be a little unfair, as most places fall short of the standard set in the northern Netherlands city and Nottingham cannot claim automatic status in the premier league of English cycling cities, such as York, Cambridge or Oxford. But truth be told, it is probably a more typical example of the efforts being made by British local authorities struggling to get more than a tiny proportion of the population out of cars and onto bikes. In many basic respects though, the cities are broadly similar, so in theory there is no inherent reason why Nottingham couldn’t become the UK’s first Groningen. Both cities are ‘county’ capitals with a population in the greater urban area of between 400,000 and 500,000. Both have some income from tourist visitors but both are predominantly working towns where the transport network is for the use of people who live and work in the area.

GRONINGEN - a true network. Cycle routes are mostly segregated and link the heart of the city with outlying suburbs, industrial estates, schools and leisure facilites

GRONINGEN – Gridlock to Cycle Nirvana

Reading about the city’s rise to star status in cycle usage terms it becomes clear that Groningen’s hallowed reputation is no accident. For much of the 1970s it was feared that growth in motor traffic would overwhelm the city and at that stage there was no reason to suppose they would progress beyond the UK’s current general attitude of recognising the problem but being chronically incapable of doing anything about it. Groningen’s current percentage of daily journeys by bike (often quoted at between 50% and 60%) seems to have been due to a definite and deliberate policy by the local city council based on the following:

1. Motor traffic was regulated and often deliberately excluded from certain city areas. The ball was set rolling in 1977 when the City Council sprang into action by digging up and removing a six-lane highway in the city centre to replace it with a more human landscape of greenery,Watnall bus lanes and pedestrianization. Subsequently, manyBurton roads were narrowed to reduce motor traffic speed or even shut entirely to motorJoyce traffic.Thirty kmh (19mph) limits on minor roads, and especially in residential areas, became the norm.

The key to the success of the Dutch model is that cyclists have priority to motor traffic. This is even true at major intersections, although motorists do not always obey.